Love Letter to London

(listen to this selection, read by Diane R. Wiener)

With my work, I am interested in exploring themes such as love, intimacy, and memories. Most recently, my work is inspired by the profound love I share with my Guide Dog, London—we have an interdependent relationship that crisscrosses between maternal, spousal, emotional, and practical—a bond which I believe transcends the traditional binary between pets and owners.

Since I’ve just started the process of applying for a new dog, I’ve been reflecting on the nine years London and I have been together. She is my first Guide Dog, and I get very emotional when I think about having to replace her. London was born in 2010, only two months before the traffic accident that caused my blindness. I know it’s silly, but I sometimes imagine that we were meant for each other, and that she would one day grow up to become my Guide Dog, my muse, my partner in crime, and one of my closest companions.

I met London, an English Labrador Retriever on August 5, 2013, the day after my 24th birthday, and at the start of my final year at The Cooper Union School of Art. When my trainer brought London into the apartment, she made a rush towards me, excitedly sniffed me all over, my hands, legs, and feet—I then listened to her nails click around my living room and kitchen, smelling everything in her new surroundings.

For the next two weeks, we learned the route to school, the studio, on busses, and subways across town. Learning how to travel with London was so exhilarating. I walked faster, with more confidence. Through her harness, I followed her graceful movements as she effortlessly glided down the busy streets of New York City, dodging hordes of people and sidewalk furniture. Through the harness she could also feel my grip tighten as we neared a corner intersection. She waited, as I listened to the sounds of traffic for the right moment to signal for us to cross. As a blind and profoundly hearing impaired person, I was given a new sense of safety and autonomy, and I could tell that she also loved working with me. Our bond strengthened over time as we got to know each other’s personalities, needs, and desires, through a communion built on mutual respect, care, and trust.

In 2017 London and I moved to New Haven for grad school. I wanted to leave my comfort zone, but it was also scary—being in a new city, with new people who didn’t know me, or how to best interact with me. There were some funny instances, like when London developed a habit where she’d stop in front of my classmates’ studio doors that were left open. London would pop her head in to see what was up, look cute, and wag her tail at an unsuspecting classmate who’d either be working or eating lunch in their studio. This was a little awkward, but always made us laugh. There were other times when I missed out on socializing. At nights, my cohort would go to the dive bar on the corner to let off steam. In the beginning I tried it out, but socializing at a loud bar, with multiple conversations going on at the same time was more exhausting than fun for me. Because of my hearing impairments, settings like that can often be traumatizing, making me feel more isolated than included.

I was hopeful to meet disabled students from other departments who might be going through similar things, but the school didn’t make it easy for disabled students to connect with each other, nor did I meet any disabled professors and faculty members. If there was ever any sort of organization, or events for students with disabilities, the school did not advertise them the way it did for other group organizations and events. I thought I would finally meet people when I enrolled in a class focusing on Disability Studies, but was so disheartened when I learned that there were only three other people in the class, and that I was the only one with a disability. Feeling like the only disabled person in the school was the hardest part. But later I would find myself in theoretical texts and memoirs by disabled writers, and be introduced to a Crip art community outside of school through Instagram and Zoom.

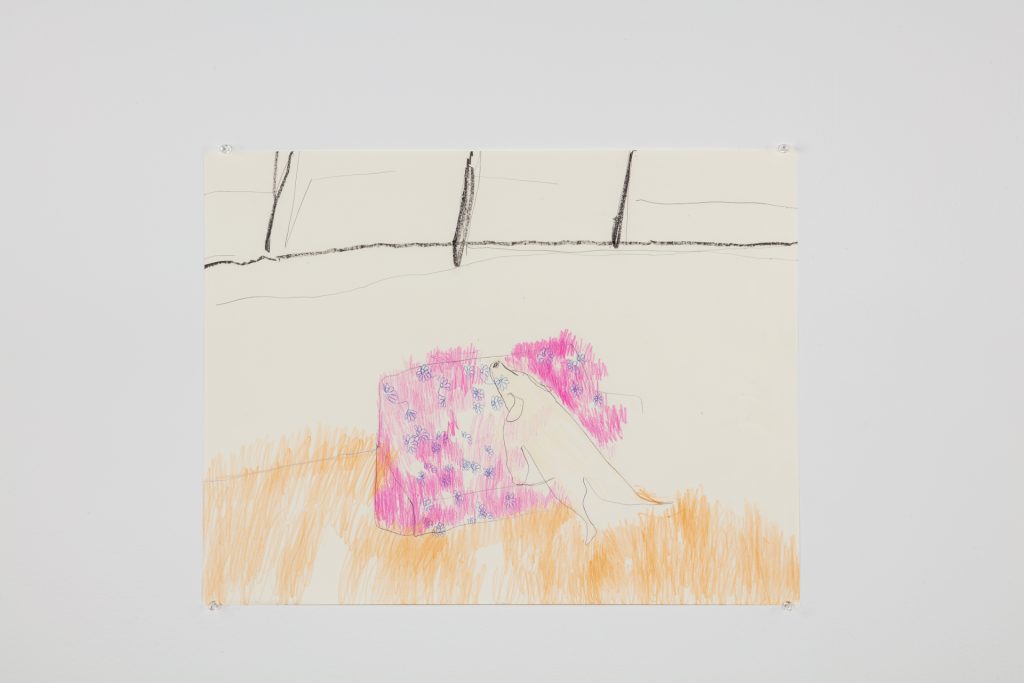

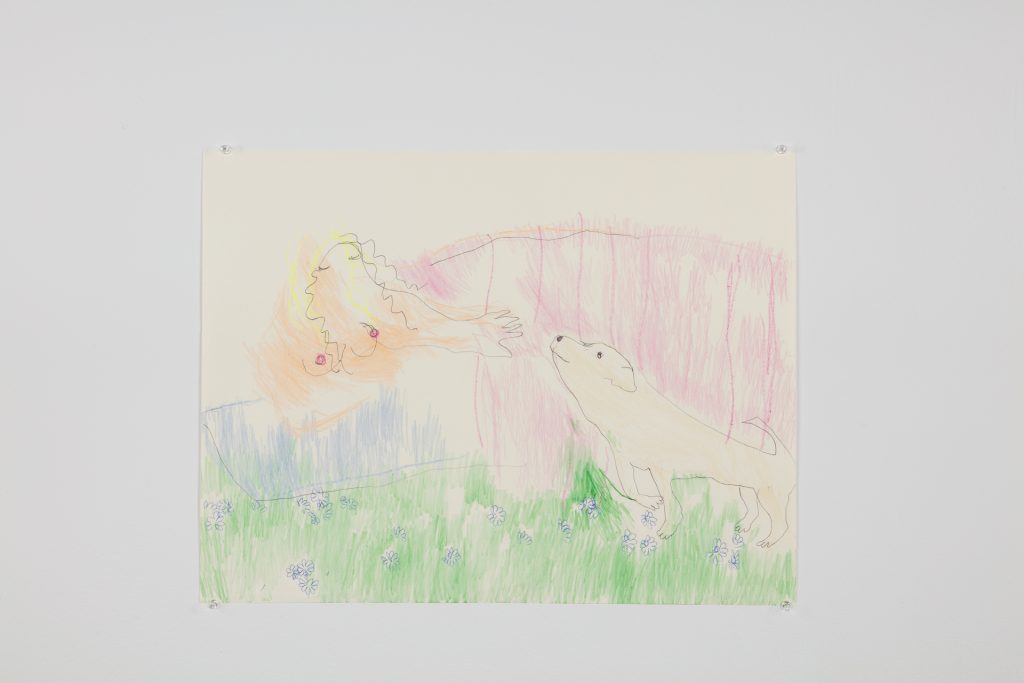

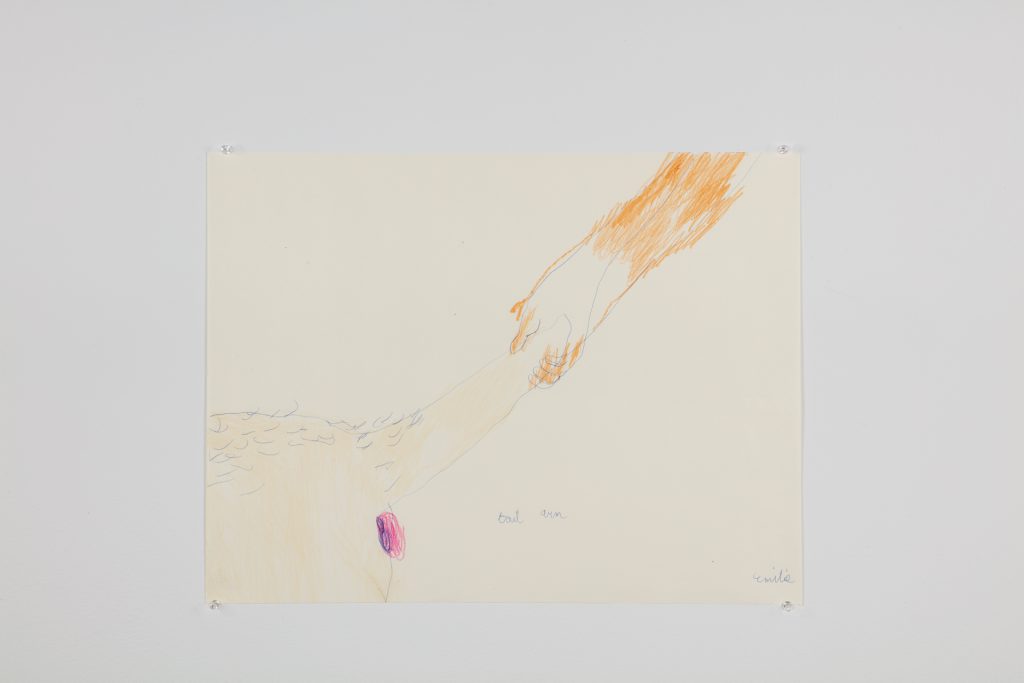

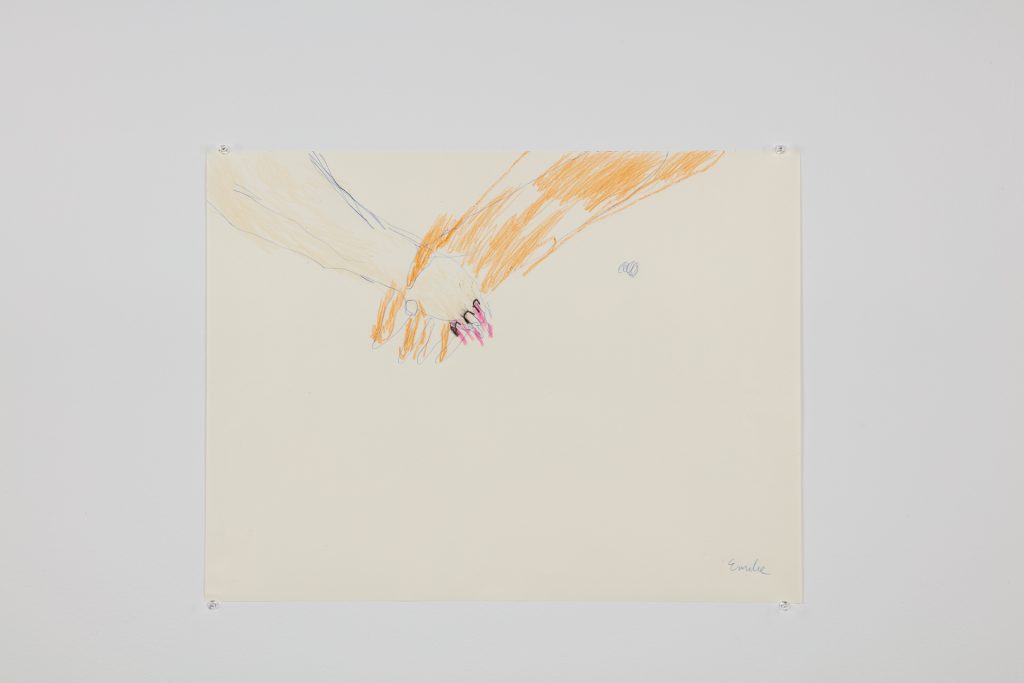

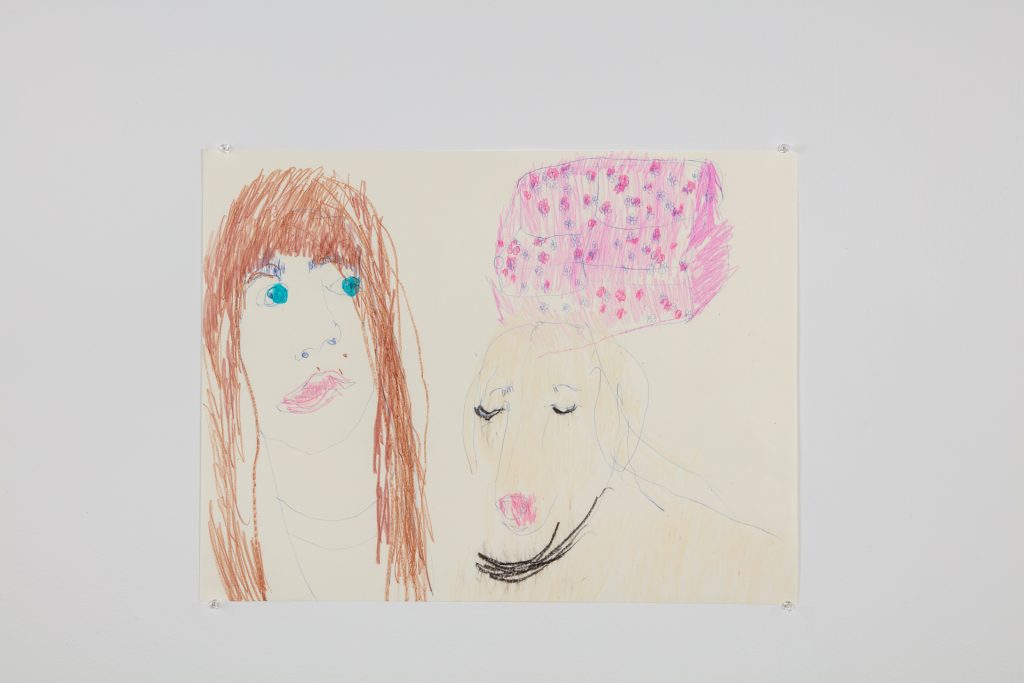

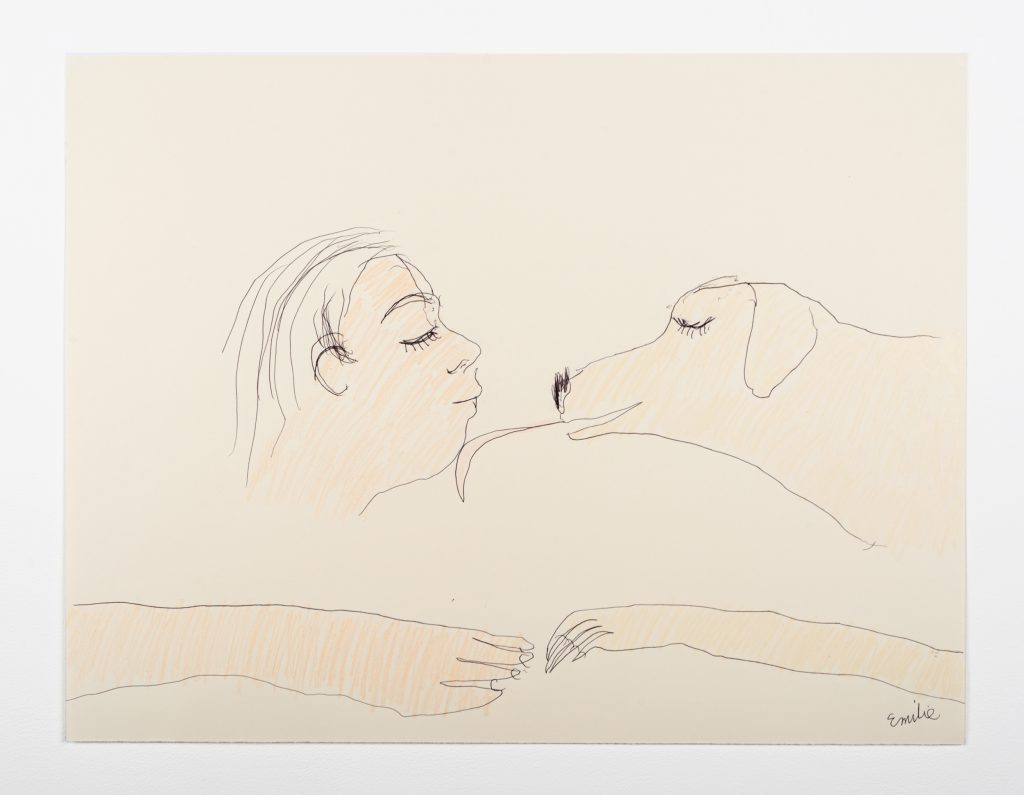

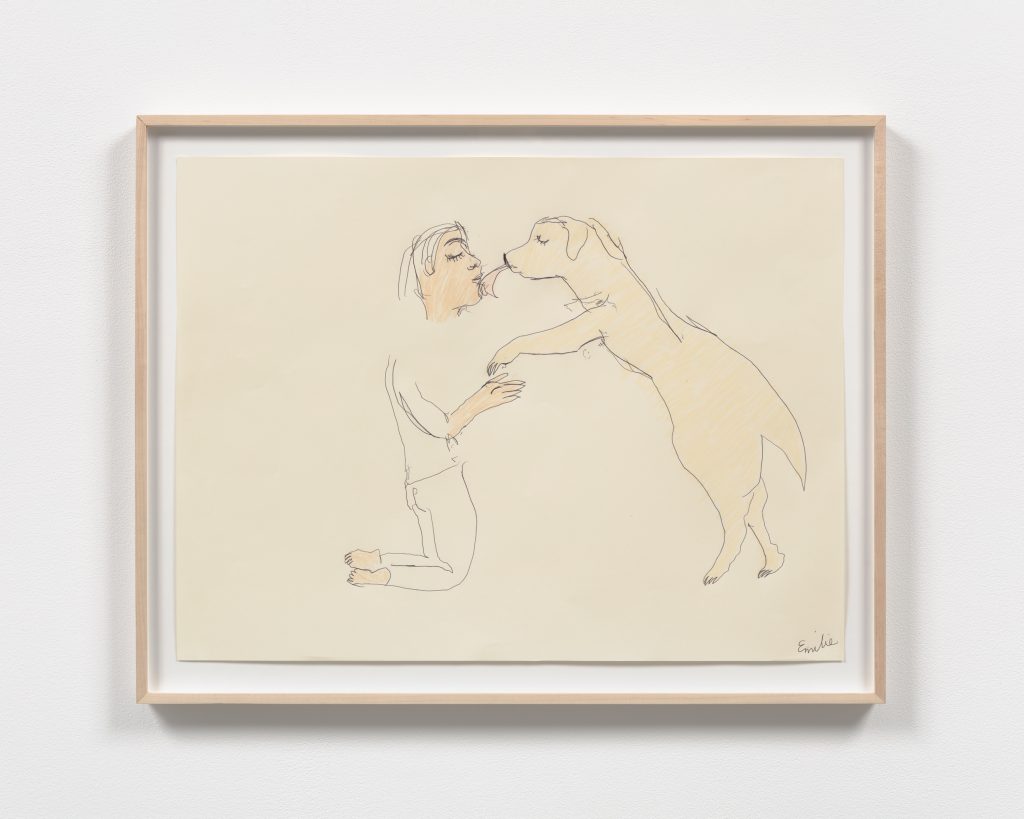

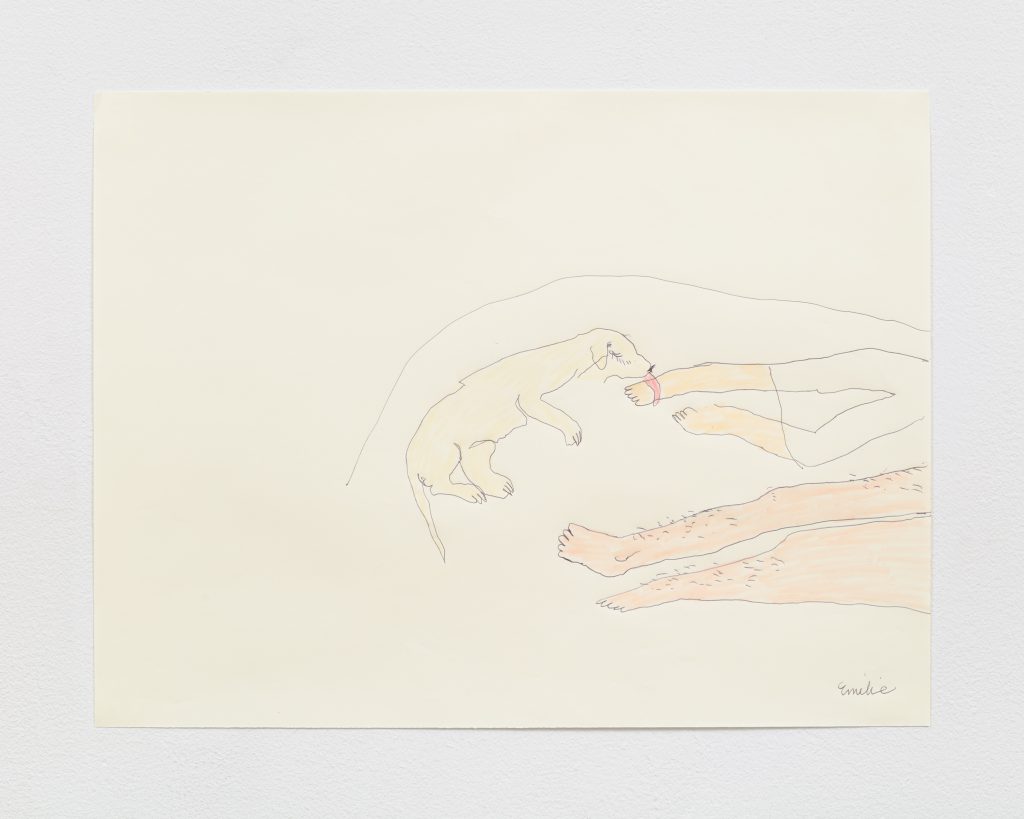

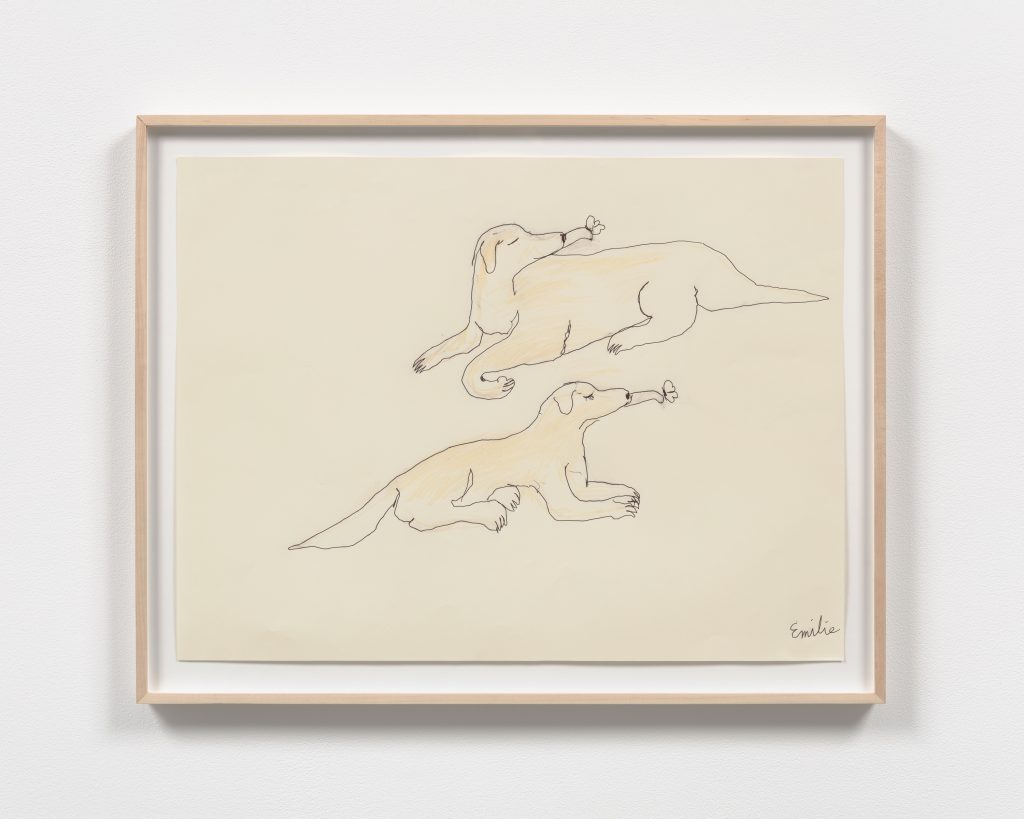

During these lonely times, London became my closest friend, and I began to see her as an integral part of my emotional and physical well-being. She was involved in my imaginations— I started to make drawings of London that captured her personality, and our playful interactions with each other—(“Arm, Tail, Butthole”, “London Mounting the Couch,” “Hand in Paw,” and “Butterfly Kisses.)” I also made drawings of London’s exaggerated long and pink tongue licking feet, hands, and faces, depicting the sensual and intimate side of our relationship—( “Tongue to Chin, Hand to Paw,” “The Good Girl,” and “On a Good Day You can Feel My Love for You.”)

A group of these drawings are part of a traveling exhibition, Crip*, curated by Liza Sylvestere, at the Krannert Art Museum in Champagne, IL, and Gallery 400 in Chicago—a group show I was proud to be part of with other incredible artists—Shannon Finnegan, Carly Mandel, Berenice Olmedo, and Alison O’Daniel (to name a few).

Also included in Crip* is half of “Dancing with London” (2018), a sculptural installation of two Londons standing up on her hind legs, front paws extended out in front of her body as if leaping into the air, with her long tail extended in an elegant swoop behind her. Her paws are sculpted with each individual toe and smooth glossy nail, with a soft rubbery pad under her paw for the viewer to hold onto as they position themselves in front of London. She has a serene look on her face, and her eyes are closed, like she’s waiting for a kiss.

This sculpture is a monument to London, a memorial to our younger, and happier, times. Back in undergrad, London and I were both hard working girls, but we also liked to get rowdy when we played together. At night when we got home from the studio, I’d plug my iPhone into the speakers, turn up the volume, and we’d dance around the apartment. London jumped up on her hind legs, placed her paws into my open hands, and I held her up as I swayed my hips side to side, while she wagged her tail to songs by Robyn, Le Tigre, or Grimes.

This piece was conceived when I was forced to think about London’s mortality for the first time. In 2018 I took London to the vet for teeth cleaning, because she was bleeding in the mouth. The surgeon removed some teeth that were coming loose, along with tumor-like growths they found on her gums. The vet scraped them away to perform a biopsy, but warned me that it could potentially be mouth cancer. I would have to wait a week for the results. The thought of losing London was devastating.

Later that day, my partner Kirby picked us up from the veterinarian clinic in New York City, and drove us back home to New Haven. London slept in bed with us every night, and we gave her antibiotics and pain killer medication until the doctor called with the good news. The tumors were totally benign! It was just a very ugly case of gum disease. I’ve been brushing London’s teeth ever since, so that it never happened again. In 2021, I recreated “Dancing with London” for the Crip Time exhibit at the MMK Frankfurt, where it was installed in the atrium with a mural, “Hand Palm,” by Christine Sun Kim—an honor to show with her and many more Crip artists whom I love and admire.

“True Love will Find You in the End” (2021), my commissioned piece for The Shed’s Open Call, is another monument to my deep love for London, and a response to my feelings about the intersectionality between the experience of disabled people and non-human animals. During the start of the coronavirus pandemic, it was emotionally painful to read about the way disabled people’ were receiving less care, and were viewed as expendable the way thousands of livestock animals were slaughtered because American meatpacking factories were shut down. I was reminded of the time someone I was close to dehumanized me by comparing me to a dog, needing to be walked and cared for by someone every day because of my disability. I thought of all the times I had to face discrimination for traveling with a dog, being denied access into restaurants, taxis, and shops, which is always so infuriating. And I was reminded of the one day I overheard my neighbor talking into her phone, calling me “the blind girl with the dog,” when I only needed to take the elevator one floor down. She was annoyed that I had taken up so much time and space in the elevator with London, which made me wonder if this was how everyone in the building thought of me—a nuisance.

With “True Love” I wanted to dismantle the hierarchy between non-disabled and disabled people, as well as the hierarchy between humans and animals. The sculptures meld my human form with London’s as a way to embrace the beautiful animal side of myself, and when I think of London and myself together, we become a whole, a super-being.

“Disability Futures in the Arts” is supported by the Canada Council for the Arts/Conseil des arts du Canada.

Back to Top of Page | Back to Disability Futures in the Arts | Back to Volume 16, Issue 4 – Winter 2022

About the Author

Born in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1989, Emilie Louise Gossiaux is an interdisciplinary artist currently based in New York City. Gossiaux earned her BFA from The Cooper Union School of Art in 2014, and her MFA in sculpture from Yale School of Art in 2019. Her solo exhibitions include, “After Image” at False Flag Gallery in Long Island City (2018), “Memory of a Body” at Mother Gallery in Beacon, NY (2020), and, most recently “Significant Otherness” at Mother Gallery’s location in Tribeca, New York City (2022). She has shown her work internationally in multiple group exhibitions at museums and venues such as The Wellcome Collection (London, UK), 1969 Gallery (New York, NY), The Aldrich Contemporary (Ridgefield, CT), MoMA PS1 (New York, NY), Gallery 400 (Chicago, IL),”, The Krannert Art Museum (Champagne, IL), Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt (Frankfurt, Germany), The Shed (New York, NY), SculptureCenter (New York, NY), Julius Caesar (Chicago, IL), Pippy Houldsworth Gallery (London, UK), and Recess Gallery (New York, NY) among others. In 2013, Gossiaux was awarded a VSA award of Excellence from the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, the Eliot Lash Memorial Prize for Excellence in Sculpture in 2014, a Wyn Newhouse Award in 2019, and most recently one of 10 artists to be awarded the Colene Brown Art Prize by the BRIC Art Center in 2022. Gossiaux has been featured in publications such as The Brooklyn Rail, The New Yorker, Art in America, and Topical Cream Magazine.