WG: Thanks for agreeing to meet with me, Mallory! Can you tell Wordgathering readers about the National Disability Theater’s inaugural production, Emily Driver’s Great Race through Time and Space (and why you also call it “Emily Driver’s Disability Revolution”)?

Mallory Kay Nelson (MKN): Yes! I can also tell you about Alice in Wonderland and primarily to the moon and back. Emily Driver’s Great Race through Time and Space is the first children’s touring showcase by all disabled artists. It is about America’s 1977-1979 disability history and the laws in America that helped ME get educated—and to have access to education.

WG: You?

MKN: Personally.

WG: Oh, okay.

MKN: I learned how to read because of the 504. And I can ride the bus because of the 504.

WG: What do you hope children will learn from this experience of the theater?

MKN: That the disabled are human beings who have fought for our rights and that we need Transmobility to move freely in our worlds.

WG: Thank you. So, why do you call the production “Emily Driver’s Disability Revolution”? And, what do you mean by Transmobility?

We will link on the Wordgathering site to the great article (“Transmobility: Rethinking the Possibilities in Cyborg (Cripborg) Bodies” in Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, and Technoscience) that you co-authored with Ashley Shew and Bethany Stevens. [Editor’s Note: Brief image descriptions (based on Catalyst article’s alt-text) of Mallory’s art pieces featured in the article are included below.]

MKN: All bodies of actors are alive. They move freely through theatre space. I am transmobile during a tech rehearsal to get to the audience seating, the directors and other designers, etc. You can elaborate that. I also must get to the stage, back stage, and to costume stock in the [costume] shop, all within a moment’s notice. These spaces are nearly always inaccessible, and I cannot get to all of them with the same mobility tool.

I call the production “Emily Driver’s Disability Revolution” because, basically, it’s a revolutionary war that we are in right now, to have access to wheelchairs and other mobility tools.

This play just points out several of a few oppressions the disabled live with in our daily lives. And although we are framing the play from the perspective of a disabled tween, there is a full breadth of disability history included in the performance.

I have had similar experiences to this character since I was a kid. It’s one of my personal stories on stage, and this is why I costumed Emily right out of my own closet. I even put her in Mallory Green.

WG: Can you describe Mallory Green? Also, can you please provide some examples of costumes for this show and explain a bit about your aesthetics as a disabled costume designer in this particular context?

MKN: Mallory Green is the lime green shade I dressed myself in after I lost my leg, and to define my identity outside of my new physical disability. I’m the costume designer that designed my own clothing in high school to be me.

WG: Can you share a little more about that, if that’s okay?

MKN: I became a costume designer in eighth grade when I learned how to thread a sewing machine and went home and made an Elizabethan gown—like yah do! [Mallory and Diane laugh.] No idea how to use patterns, just a measuring tape and me and some fabric. And, voila! Halloween costume number one. This just led into—I mean, I think the most interesting thing about Queen Elizabeth I’s costumes is that she literally had a stool built into some of her dresses, so that while she was parading down the street, she could sit down, when the jeweled garment that she was wearing weighed over 300 pounds. These things just became fascinating, instantaneous…

WG: She cripped her costume!

MKN: Yeah, she cripped her costume, and we know that she had fevers, and the wigs, and the like…Queen Elizabeth! She was one of us!

So, knowing all these things, early on in my life, and then having this moment where I’m starting puberty, and to then be in a catastrophic car accident that by all means, if it weren’t for some really invested doctors, I never would have survived. And, coming back into what would have been my freshman year of high school, trying to somehow be essentially for the next three years recovering from this catastrophic accident, and just being able to play back at school and control what people thought of me in some way or another, because there wasn’t another amputee wandering the hallways, there was no other wheelchair user at my school.

Later, I was at the Denver School of the Arts. So, there, in a way, everybody was an Other, and to stand out amongst the Others was my hobby. The previous year, I had literally carried around a container of jello, called it the Green Jello God, and just brought it to school and stuck it in the fridge every single day, like a ritual. And, I took pictures with the principal, took pictures with the teachers. I have a whole photo collection of the Green Jello God in different places doing various things.

WG: Some people have Flat Stanley. You had the Green Jello God.

MKN: Yeah! So, green’s always been my thing. I decided green would be my favorite color when I was like, “Wait, I’m supposed to have a favorite color. What color will it be? Alright, I’m gonna go with green, because it’s not gender specific.” Where that idea came from might have been because I was raised in a gender neutral household with a mother who loves literature, and a father who was an architect…and I got to paint my room whatever color I wanted.

At that time, between becoming pubescent and becoming a teenager, that threshold in the middle, having a colossal catastrophe happen to me, I went from my lime green bedroom and took over my brother’s bedroom, because it was bigger, and I was essentially going to be in that bedroom, so much of the time. You know, withdrawing from morphine and rebuilding all of my muscle strength again and recovering, hoping that different parts of my body would come back online, having a mother who was able to take on the responsibility of a full-time caretaker. And just like, somehow, my family managed that without any extended family, because we were in Colorado and all of them were here, in Liverpool and Utica, New York.

This all translated and rolled into me, then having to have a new body. Knowing how to use patterns and a sewing machine, at that point. Having fabric. We bought me a sewing machine and sewing table after surgery, as part of my rehab money, and I was able to take the fabric that we bought, one of which was a lime green plaid—oh, that fabric is gorgeous, there must be some of it hiding, somewhere. There are pictures of me in those pants, I would build myself cargo pants. And I would build myself other things that I needed in order to be the technical theater person I already was. I made my own tech pants, I mean, because you can’t buy pants with one leg. The art form of figuring out what to do with an extra pant leg is still something I am perpetually playing with. Right now, today, I’m wearing a pair of jeans that I got one of the stitchers in the Syracuse Stage costume shop to do a proper fitting of…I don’t actually have a right hip to hold my pants up.

So, I live in this land where clothing…I do not put my pants on the same way as anybody else. And, frankly, I prefer actors that don’t put their pants on the same way as anybody else. And, if one more person tells me that we all put our pants on the same way, I’m going to showcase a music video of amazing people putting their pants on in the strangest ways you’ve ever seen.

WG: So, the secondary title of this interview is now, “Different Ways Pants Can Be Put On, Green or Not.” [Mallory and Diane laugh.]

I want to ask you to talk about your t-shirt choice for Emily, the main character in the NDT production. How is this trajectory you just described related to your t-shirt choice? I know that t-shirt was designed by a disabled artist.

MKN: I have a habit of glomming onto interesting disabled people. [Diane laughs.] I think I can spot them in a room.

WG: You have cripdar.

MKN: Yes! So, there was this man, he wasn’t moving much, so naturally I have to come up to him, accost him (that’s a hobby of mine—just ask my friend in third grade how we met…because I followed her home from school). So I just glommed on. I was like, “I need to know everything about you, who you are, what you are doing here. Tell me. I need to know.”

WG: You were at…

MKN: You know, the awesome CripCon. [Mallory smiles broadly at Diane.]

[Editor’s Note: “CripCon” is short for “Cripping” the Comic Con, a disability and comics symposium co-created and co-coordinated by Rachael Zubal-Ruggieri and Diane Wiener, held at Syracuse University.]

WG: Yeah, I know about that. [Mallory and Diane share a thoughtful pause.] Thank you for that.

MKN: Well, I need disability space. It’s my lifeline. And, If I don’t have it, I’m missing something, missing an entire fluid in my system. So, I glommed onto this guy and then I learned everything about him. And then we started becoming best buddies, really quick. I started downloading everything I could mentally about who he was, his identity, what he was up to, what he’d been doing. Then, I’m like doing some kind of a mad research project—because I’m just so over the internet, until I can Google “disability” and have something other than “social security” and “lawyers” come up.

So, I looked up Mike Mort—there you go, he has his own online space for you to get t-shirts, and he is this brilliant graphic designer, you can’t even imagine! And, you also can’t imagine how he’s doing it. Mmhmm. I’ve never seen a graphic designer do what he does. That approach just doesn’t exist, except with Mike. There is nobody else doing exactly what Mike Mort is doing.

WG: So you chose to put Mike’s artwork on Emily’s t-shirt, for the NDT production?

MKN: Yes. Mike’s work represents the new disability shirt. The new clip art. It’s very important to me that disability is represented by either allies that respect the culture or by disabled people themselves. Mind you, it’s a smash bag of ableism out there.

Somehow, creating a character like Emily was connected with whatever I imagined was in her closet, at the time, and, most likely, she’s a total computer nerd. She’s obsessed with the American Revolution. She’s a preteen and doesn’t represent anything particularly unique about the preteen experience, other than that she’s having the preteen experience while dealing with her unique body. A body that’s not “complying” to the inaccessible spaces.

WG: Wearing the t-shirt that Mike Mort—from Liverpool, NY—designed.

MKN: Yes. And it’s part of Mike’s older collection, the one with Wonder Woman.

WG: Wonder Woman using a wheelchair.

MKN: Right. So, for people who are not familiar, this work stems from the new symbol for disability access—especially used in the U.S.—an active wheelchair user, with the torso in action, the elbow going back. I think Mike and his work added the arm going forward.

WG: It’s not a static image like the older image for access had been.

MKN: Right.

WG: Yet this symbol is a particular kind of representation of disability, while it references a multiplicity of disabilities. It’s still highlighting a particular set of experiences. Okay. So, Wonder Woman using an active wheelchair symbol…

MKN: Yes, and with her belt, and her golden lariat…her cufflinks…she’s pushing forward…she’s hot, she’s got the breasts… Mike is a guy who knows how to illustrate a woman’s body, quite thoroughly, using accurate stylizations of comics, with graphic design techniques and proportions. He does it naturally. He’s never had any formal training—this is all just what he has come up with and figured out how to do on a computer.

WG: Which is why we were so happy that he joined us at the CripCon.

MKN: And I’m obsessed with him.

WG: Since this interview is going “to print” [online], I assume he probably already knows that you are obsessed with him, and that it’s okay if it’s public knowledge?

MKN: Yes, and, at this point, we think his mother is okay with me, too. “There’s that person that shows up sometimes, that we can’t get rid of,” maybe she’s thinking. That’s me!

WG: So, Emily, the protagonist in the NDT production, brings together the real and the imaginative, and your friendship with Mike. The character is wearing a green color scheme that’s connected to your history, personally. She’s wearing a t-shirt designed by your close friend and my esteemed colleague, Mike, a disabled graphic designer. The audience is brought into relationship with these historical and biographical experiences in a fictional story based upon very real events—advocacy for the signing of 504.

For people who are not experiencing the performance visually, how do they access the visual elements?

MKN: The National Disability Theater set it up so that at the beginning of the play, the actors introduce themselves to the audience and they describe the costume pieces and the set. I don’t know who deserves credit for that, but it’s a brilliant idea.

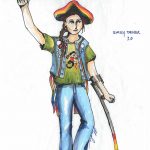

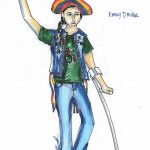

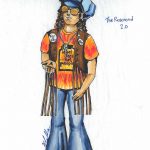

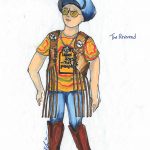

[Mallory shows Diane some of Mallory’s original sketches for the production, including a character wearing a Label Jars Not People t-shirt. Editor’s Note: Seven of Mallory’s full-color sketches are reproduced, below, with accompanying image descriptions.]

WG: From the Human Policy Press, connected with the Center on Human Policy, at Syracuse University! Led originally by Burton Blatt!

MKN: And I got the print from Teddy’s Ts.

WG: Nice. So, how did you go about designing some of these costumes?

MKN: Emily is a transmobile character. I took a long look at the history of protest, thinking about all of the different cultural backgrounds, all of the people who were involved in advocating for the passage of 504. The Black Panthers working with the disabled protestors. The history connected with the Independent Living movement, Ed Roberts, and so on. You know, the collective of now educated disabled people, and the mecca of disability history in San Francisco. There was enough stubbornness and there were enough people to be able to sit in an office for enough days to make sure it got so uncomfortable.

One of the characters, Lady J, is based upon Judy Heumann. I designed Lady J’s octagon eyeglasses as a tribute to Judy’s!

I researched a lot of photographs from that time period and took it from there. Like this photograph [Mallory shows Diane a classic black and white photograph from the 504 protest], at the eye level of a wheelchair user, taken by Anthony Tusler, a wheelchair user, in the absolute traditional look of protestors in San Francisco in 1977. With signs. And buttons.

WG: [Diane references the photograph.] This person is wearing a button that says “SIGN 504” with “Handicapped Human Rights.” That would make a great t-shirt!

Can you tell me a little bit about how you decided to become a costume designer? So, when you were 13, you were already sewing an Elizabethan costume. Soon thereafter, you were recovering from a nearly fatal accident that changed your life forever, and you were going through all of the machinations of what it was like to be in this room that used to be your brother’s, a bigger space you needed for your recovery, and everything you said about that—how complicated and difficult, which is an understatement. So, when did you know that you wanted to be a costume designer?

MKN: The second I learned how to thread a sewing machine. Because I saw…I don’t…I don’t think I understood what I saw. I am just, you know, making up words, at this point, of what it might have been [like], what I saw.

WG: What did you see?

MKN: Power. I saw control. I saw information in mass quantities without any words being said. The words were made up.

WG: Wow. So, the words are never part of nature, they weren’t the point. The images were the point, and the creation of the tactile experience was the point.

MKN: And the beauty of the merging of like, mountains, clouds.

It seems that Queen Elizabeth I may have had a garment that had eyes, ears, and a mouth on it. A painting depicts this garment, but whether or not the original tapestry had those elements actually woven into the fabric, or whether they were added by the painter, we don’t know. But every inch of her garment and every single portrait is telling you something. It’s telling you about her control of the world, her marriage to England, her role in imperialism, her choosing no husband and having no children past her point of reign. It is telling you about the fever she had as a child, her disability. It’s all about proportions, and the control of women’s bodies.

Let me just tell you where all the pockets have been hidden, this whole time, and the control and oppression of disabled and nondisabled women through pockets [and their absence]. From the beginning of history.

Brief image descriptions (based upon article’s alt-text) for Mallory Kay Nelson’s artwork in the Catalyst article cited above (“Transmobility: Rethinking the Possibilities in Cyborg (Cripborg) Bodies”):

- Black and white sketch of a woman sitting sideways on a wheelchair

- Black and white sketch of a woman using an electric wheelchair.

- Black and white sketch of a girl dancing.

- Black and white sketch of a woman walking with a prosthetic leg.

- Black and white sketch of a woman on a rollator.

- Black and white sketch of a woman on crutches.

- Black and white sketch of a woman sitting in a wheelchair.

- Black and white sketch of a woman standing with a prosthetic leg.

Note from the Editor: The seven thumbnail images included and described below (which can be accessed/viewed in larger sizes, when selected) are digital reproductions of Mallory Kay Nelson’s full-color costume design sketches for the La Jolla Play House and National Disability Theater’s 2020 production, Emily Driver’s Great Race through Time and Space (by A. A. Brenner & Gregg Mozgala; Directed by Talleri A. McRae & Mickey Rowe). These images are shared, here, with the permission of the artist. No reproduction is allowed without direct permission from the artist, Mallory Kay Nelson.

About Mallory Kay Nelson

A whimsical visionary and relentless advocate, Mallory Kay Nelson makes space for disabled people to thrive. Self-educated in the field of Disability Studies, she dedicates herself to spreading its gospel. Mallory holds an MFA in Costume Design from Carnegie Mellon University. She designed costumes for the PHAMALY Theatre Company for six seasons and received Henry and Ovation Award nominations for her designer work on Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat and The Wiz. Mallory’s design work represented the U.S.A. at the Purag Quadrennial and has been showcased in New York, Los Angeles, Washington D.C., and Moscow.

Mallory enjoys crashing scholarly conferences and appearing in places you wouldn’t expect. She has worked as a Vocational Specialist for Easter Seals, performed ethnography for Smart Revenue, assisted with community relations for Diverse City Entertainment, consulted on marketing for Push Girls, guest lectured at various universities, and assisted with AHEAD.

Following her role at Easter Seals, Mallory joined the National Office of USITT as the Membership & Education Assistant. She also served as Assistant Costume Shop Manager and Costume Coordinator for Syracuse Stage and the Syracuse University Department of Drama (in the College of Visual and Performing Arts). In 2015, Mallory joined the Board of Directors for the Society for Disability Studies (SDS). Self-described as an “SDS version of a pinball game,” Mallory notes that she “bounces off bumpers, kickers, and slingshots at every turn, sometimes hitting the target, and at other times falling off the playfield.” In all of these ventures, among others, her “honey badger-esque” manner and solidarity with her fellow crips have never wavered.

Back to Top of Page | Back to Interviews | Back to Volume 14, Issue 1