This interview took place in September 2021 after the exhibition Sutured Resilience closed at Artworks in Trenton, NJ. Sutured Resilience brought together artists Jennifer Cabral, Kat Cope, and Chanika Svetvilas, who explore trauma, memory, and empowerment to imagine a reality that finds strength in vulnerability through text, photography, sculpture, drawing, mixed media, video and participatory actions.

Diane R. Wiener interviewed Chanika Svetvilas and Jennifer Cabral for Wordgathering, via Zoom. This Zoom recording transcript was edited collaboratively by the three of us. Chanika Svetvilas is a previous contributor to Wordgathering (Spring 2021 issue), and introduced Jennifer Cabral and Kat Cope to the journal and Diane Wiener. (Kat Cope declined to be interviewed.)

Photographs courtesy of Jennifer Cabral, except final charcoal drawing—courtesy of Chanika Svetvilas.

WG: I’m delighted to be here, today, with two artists with enormous talent, both of whom I hold in very high esteem. We’re very honored to host a conversation with you–in the spirit of Crip arts and culture–for Wordgathering. Would you kindly say a little bit about yourselves? Thank you.

CS: Thank you for holding this space for us. I define myself as an interdisciplinary artist and I work at the intersection of mental health difference and neurodiversity. I tend to go back and forth, with different terminology, and sometimes it even depends on the context in which I’m speaking. And I work in a variety of media, because it really depends on the concept or theme of the work. Mixed media, collage, drawing, sculpture, installation, video, the list goes on. However, I’ve been doing mostly drawings and sculpture and some video during the pandemic. The common thread is using readymade objects like prescription bottles, medication guides, medical texts and my personal archive. I also create interactive work with my audience. As participants, they complete the work. Unfortunately, during Covid, I haven’t been able to do those kinds of interactions.

My work intersects with my lived experience with mental health difference, while my previous focus was more on my Asian American identity as someone who’s Thai American and whose parents were immigrants. But because of how I was impacted when I was in graduate school (which I probably don’t have to go into too much detail about, because it’s a bit of a lengthy story), while I was pursuing my Master of Fine Arts in Sculpture, I had a bipolar disorder manic episode and I was hospitalized and released.

Although I was able to re-enter the program, the short version of my story is that I was dismissed from the program. And my thesis committee said it was in my best interest. And until that point, I had internalized ableism and really had a difficult time accepting my diagnosis and what it meant to me in terms of how I was fighting that condition and how it was impacting me.

And it wasn’t until I was confronted by that kind of discrimination that I really had to address my relationship to my bipolar disorder and mental health difference and it motivated me to ask those questions through my art and to explore what what my neurodiversity meant to me. And so there was a whole shift in my work that wasn’t there before and there have been other shifts too from focusing on awareness, because I think being kicked out of graduate school–which to me felt like it really was because of a lack of understanding of my abilities–that I I felt I needed to raise awareness.

But, during Covid, I realized that’s not enough, because you can raise awareness, but that doesn’t mean any change or shift will happen that will make a difference. Now I try to explore ways that I’m speaking to my community, so the audience isn’t people who don’t identify with disability or mental health difference, but that my audience is people like me.

WG: I thought that was great, and I want to ask you about 17 things, but we want Jennifer to introduce themself, now. But, I’m going to bracket, briefly, and say out loud (and then of course the captioning will help us in the accessibility of the conversation) that, that, I would say the art of mutual aid is what came up, as I was listening to you. And I’m just very glad to have heard everything that you just shared, so thank you very, very much, Chanika. Jennifer, hi. Would you honor us by telling us a little bit about yourself and your work? Thank you, so much, both of you, again.

JC: Thank you, so, for having us in Wordgathering. My name is Jennifer Cabral. I’m a photographer primarily, but that definition has been changing for me, especially in the past five years. I’m incorporating texts and recordings, even dabbling with painting, which I never did before. My formation was in art. I have a BFA from Escola Guignard in Brazil and was exposed to all techniques, but my major was in photography. I moved to the United States in 2001. So my whole foundation in art was in Brazil. This was a very small school. We had a library, which was our bread and butter, and our main way to have access to art. Traveling exhibitions were sparse and contact with the world art scene was limited. But that was 20 years ago. Now, national and international exhibitions are common and the Internet offers a whole different context for art foundation.

But, back then, seeing works by other artists was limited to books. Looking at paintings in books is painful and unrealistic, because you don’t have any reference of the color, texture, dimension–you lose all that. So coming to the States and having access to the array of art institutions and galleries was a bit overwhelming. I’m going to say that it prevented me from going into other techniques, because I was so overwhelmed by looking at a real canvas. I felt more comfortable and safe in the realm of printmaking–woodcuts, lithographs, silkscreen–and photography.

Maybe that’s why photography became my medium, my safe territory–the printed matter and the book. So photography permeates all of my works and I’ve been pulling texts, I’ve been pulling sounds, I’ve been pulling painting as layers over my photographs. I am curious to see how far this distancing from the camera will take me. I confess that my diagnosis with cancer and the treatment that followed has shifted my whole relationship with the camera. How much equipment I can carry, my energy level– all has shifted. I don’t know if you can qualify cancer as a disability, but the disease became a container of how far I could go. And my relationship with my art changed. In the beginning the limitations were very distressing. But, I have to say that, recently, especially with the recent group show, Sutured Resilience, I feel very comfortable with the limitations. It compelled me into different territories that gave me complete freedom to intersect other mediums. A freedom I didn’t have before.

WG: Well, I’m not the arbiter of what things mean, of course, but, for what it’s worth, I definitely believe that you get to decide what your identities mean related to embodiment and emotional variance and mental health and whatever experiences you have, as a consequence of the aftermath of and the enduring in the aftermath of cancer, and what you described just now.

Maybe the identities of emotional and mental variance don’t apply to you, in which case that part of what I just said would be irrelevant, and I don’t obviously insert my perception, since that’s not ethical, but personally when I think of people who have endured cancer, every single one of those individuals, of course, has a very unique and specific experience that intersects with their own biography and their experiences are each different, in terms of in their life, when it occurred and what was happening. And so, your description of… Well, I want to say something else, but I’m going to pause and ask if it’s okay what I’m saying so far, because I should check, right?

[Jennifer acknowledges that it’s okay for Diane to continue, along these lines.]

The idea that the container of your experience was affected, and there were limits and boundaries that shifted that didn’t exist in the way that they did in your life before. To me, I perceive it as a description of disability arts and culture, affecting somebody’s art. That’s my opinion. I mean, many people would feel differently, of course, but what matters is what you think. I know that we had some questions that we were thinking about in relation to the collaborative work you’ve done around this exhibit, which we certainly can talk about, but I also know that we wanted to talk a little bit together about, you know, art during these times.

I’m very grateful to you both for what you have shared. A contextualization of your orientations as artists and the identities that you hold, and their interconnections and mutual informing. There’s a commitment to having the art communicate with people, and be in company. That’s an expression that I’ve been using a lot, of late, the idea of being “in company” with people. And in sharing spaces together and creating spaces together–and making spaces that didn’t exist before, and not only that didn’t exist before, but that were refused before. What better example, what an egregious example of refusal–you know–can we think of, then someone being thrown out of school for being who they are, you know, and, or, for that, being part of who they are? That raises all kinds of complicated ethical questions for me.

As somebody who works in education, how do we create environments where people feel welcomed, without it just being made up language that doesn’t have real impact on people’s lives when the actual situations arise that would require people to be compassionate and thoughtful and open hearted and responsive? So obviously I’m very unhappy to hear that you endured that. And I think it’s egregious, and I don’t mind going on record saying that.

I’m wondering if we can talk a little bit about how you met each other, and if you want to mention the trifecta [including Kat Cope], please go ahead.

JC: Well, I met Chanika during a small group show we were both participating at Princeton University. And she invited me to give an artist talk alongside her.

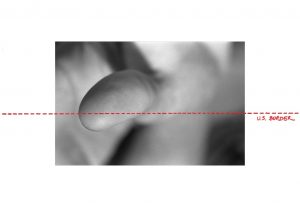

CS: Once I saw Jennifer’s work, it just resonated with me. And it was her photo series on borders, which focused at the U.S. border, the border drawn onto her body for breast cancer surgery. It was the intersectionality of her identity that I responded to. But anyway, we both gave artists’ talks, so I was able to hear more about her work and her concepts behind it. And so I think in any community you’ll always find artists, and I think artists naturally gravitate towards each other and want to meet each other. And then I was organizing an exhibition for the Princeton graduate students’ mental health initiative.

This image is part of a series of silver-gelatin photographic prints titled: “Borderline: A Manifesto”. This work juxtaposes the American Southern Border traced onto a body with a red pen. Borderline emerged from two very impactful events – one geopolitical in which a continuous wall was proposed to be erected on the southern border of the United States that questioned the rights of the Latinx community to reside in this country. The second one, was personal in which my own chest had been marked with a pen, to delineate the area that the surgical knife would remake by the removal of her left breast due to cancer. Listen to Cabral reciting the poem that accompanies this series of photographs.

My interest in working around issues of mental health difference and advocacy as well as the Counseling Center at Princeton University connected me to the student organizers, and I ended up working with them, and then they asked me to curate and organize this exhibition called Unique Minds: Creative Voices, and so I put that call out and Jennifer participated. And then I knew Kat–who is also a part of the exhibition, Sutured Resilience–through another exhibit called Sickness + Health, which was at ABC No Rio (which is a great nonprofit alternative space in New York City) and having met them both I just realized that we had something that would work collectively well together, the three of us.

JC: Because I have to thank the universe, and Chanika, because the window in which the exhibition happened was so timely. If we proposed this exhibition post-Covid, probably nothing would have unfolded as it did. It is just harder to make connections during and even after the pandemic. I am so grateful for Chanika. She had such an impact on my career. Always so supportive and encouraging of my practice. She invited me to give an artists’ talk during that group exhibition we were participating in and later she invited me to create the exhibition, Suture Resilience, with her and Kat Cope. I am amazed by your vision, Chanika, of seeing how our works would interact. It was almost a premonition of the connection we would create with each other. Recognizing how our works would just merge in such a beautiful way is really a testament to your incredible skill as a curator.

CS: Thank you. The works really spoke to each other. I mean, it was really a conversation between the works and I think it’s so important, when you see what the possibilities are that you are able to act on it. There is a lack of curators, I feel, that really are motivated to seek out work from artists that are marginalized. There’s just so much ableism, I think, in the art world, which motivated me to really think about the concepts outside of the mainstream and also, I mean, I do think with Covid there is now more awareness about being inclusive of Disability as part of the discourse and how artists who self-identify with having a disability create work. But, you know, you have gatekeepers that are choosing artists.

And so I think rather than waiting for a curator or being selected to be in a show, it’s so important that artists be empowered to exercise their own agency to create what they want to see and to not wait for those gatekeepers to recognize them, so I really felt like I wanted to create a show that I haven’t seen that I wanted to see. And that I wasn’t going to wait around for someone else to do it. And I also think it’s so important to include artists that are under-recognized, to really uplift them and include them and for everyone to have the opportunity to share their work, that it’s not just, you know, the 5%. And that everyone can benefit from seeing a diverse array of voices.

Yeah, and even geographically, I feel like you know the cities or the metropolitan areas are the ones that receive the most attention. People will even travel to New York or LA to see shows, but people forget all the artists that exist locally that are creating work.

WG: Today I’m actually going to visit the Tioga Arts Council, and I’ve been so grateful to them for hosting a plethora of wonderful exhibits which do in fact center and uplift–as you said–and raise up, but, accessibly, right? It can’t be so high–that’s one of the puns, right?

CS: Yes.

WG: It is profoundly cool. I think about the fact that I’m spending time in company with both of you, and honoring Kat as well, of course. I’m just very grateful to both of you and to Kat for the work that you’ve done. Your work impacts everyone. I’d like to go back to this idea of people talking with each other and communicating with each other through the arts as insiders. I think that that’s powerful that you said that and, of course, many people talk about that and the disability arts and culture worlds, and what’s sometimes called Crip arts and culture.

How does this exhibit, Sutured Resilience, but also how does your work in different ways separately and together comment upon Crip culture and disability arts and poetics? If you want to talk about Sutured Resilience, of course that’s great, and if you want to talk about other things, instead of or in addition, also great. Thank you.

CS: I mean, I would say, from the start, it’s also not like you’re saying, “I’m now going to create something that’s specifically related to culture,” it just is, it is a part of culture. It’s not like you’re naming it, it is a part of you, and I mean for me it’s how I choose to interact. And so we started planning back in February. Kat, who is a part of Sutured Resilience, came down to New Jersey from Brooklyn for us to visit Artworks, but we knew that Jen couldn’t join us because of the pandemic. We wanted to keep her safe and so we did our first Zoom call together, and from that time on, we met monthly via Zoom.

An important part of those Zoom calls was just the checking in and making sure everyone shared how they were doing and sometimes it was about how is the pandemic impacting us and our families and our loved ones. So it wasn’t just about the exhibit or the work we’re creating, but how we were with each other. And how we created our own bubble of support, via Zoom. And, and I feel like the choices we made in terms of:how we wanted to present Sutured Resilience that we knew, for instance, that we wanted to have a virtual space that it couldn’t just be in person, and so we wanted to create a virtual gallery, which is still up online and we talked a lot about creating hybrid programs accompanying our exhibition, but then also needed to shift that to being all online, because of the Delta variant. So, constantly being responsive and improvising, which is such a big part of Crip culture, that you improvise and you innovate, you adapt. And we all did it collaboratively.

So we had an art workshop and we moved that online and we discussed with the education coordinator about how we could have a grounding and then the education coordinator found someone who could participate with us to lead a meditation and we thought how are we going to get materials to the participants, so creating art kits and then moving our artists’ talk online. And then we wanted to do a drum ceremony and Jennifer came up with this great idea about creating a soundscape instead, which was collaborative. And she knew about a musician artist sound engineer, Doreen Kirchner, who was able to put our soundscape together. And so that was a surprising new artwork that came out of the fact that there was a pandemic, and the fact that we could no longer be in this performance space together. So, to me, it wasn’t about the subject, it was about relationships and our choices and actions. And, yeah, and how we were with each other, how we have that space together and how we also tried to open up the space to the community to try to find ways for them to participate. We had a scroll of paper that said, “what does resilience mean to you?” and the audience participated by writing and drawing responses.

The title of this work is called: Membranes. This work is a representation of how coronavirus spreads from person-to-person mainly among those who are in close contact within a 6 feet radius. This negative space where no interaction is permitted is here represented as circumferences over a series of family photos and everyday objects. An invisible sphere separates within from without. Like a cell membrane. This sphere is a reminder of the cellular connection between all matter and a symbolic shield of immunity, a sort of geometric spell so nothing penetrates our membranes.

JC: And, I’m just gonna say how for me personally, the pandemic was like…I’m going to use the term that I’m not supposed to ever repeat: it was like a reoccurrence. My status as a vulnerable patient that came from cancer, during chemotherapy, surgery and radiation when I couldn’t be in contact with others, returned. I’m still processing how much the pandemic affected me. But it made me relive the same isolation of my cancer treatment. During the pandemic I was in complete isolation, until I was given that gallery space. That was such a gift. To walk into that sacred space, that gallery, it gave me courage to step back into the world. Now looking back, I can see how the creation of this exhibition was such a picture of our times. Because it wasn’t only the pandemic. We had a hurricane and a tornado, too. Climate change directly impacted our region and the month-long schedule was constantly shifting. So we had to act as things were unfolding and trust in our ability to respond to the needs of the community.

The responsibility for the community has to come first. Our ability as artists to adapt to what is appropriate in the moment, not to an idealized vision of what we want something to be. The opening of Sutured Resilience was the first-in person event for the gallery in over a year, so the night of the opening was supposed to be a big event. But safety protocols had to be followed and occupancy had to be limited. This resistance to change, sometimes I think delays so much evolution. These times are such an incredible opportunity for change. The way art is seen, and how artists and their communities connect can be amplified in new ways now.

The Zoom sessions, for example, that so many artists engaged in during these times, were incredible opportunities for inclusion–anybody can watch, interact, and talk to each other so easily now. As an independent artist that is not part of a graduate or PhD program, I have limited access to artists and their art practice. It made me realize how institutionalized art has become. And how simple dialogue with other artists allows for such an expansion of what an art community means. Let’s hope the positive aspects of the pandemic are here to stay.

Continue reading this interview in Part II.

Back to Top of Page | Back to Interviews | Back to Volume 15, Issue 4 – Winter 2021

About Chanika Svetvilas

Chanika Svetvilas (she/her/hers) is an interdisciplinary artist based in Princeton, NJ who utilizes lived experience to create safe spaces, to disrupt stereotypes, and to reflect on contemporary issues. She has presented her interdisciplinary work at ABC NoRio, Brooklyn Public Library, Westbeth Gallery, Denver International Airport, Asian Arts Initiative, Islip Art Museum, Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning, Plainsboro Public Library, and conferences including the Society for Disability Studies, Pacific Rim International Conference on Disability and Diversity, and College Art Association, among other spaces and contexts. Her work is also included in Studying Disability Arts and Culture: An Introduction by Petra Kuppers and published in Wordgathering and Rogue Agent. She is the recipient of the New York State Arts Council’s Decentralization Grant and the Foundation for Contemporary Arts Emergency Grant. She holds an MFA in Interdisciplinary Arts from Goddard College. She is curator for the annual exhibition, Unique Minds: Creative Voices, at Princeton University and presented by the Graduate Student Government Mental Health Initiative. Svetvilas is also co-founder of ThaiLinks and Thai Takes, the first biennial Thai film festival in New York City. For more information, visit chanikasvetvilas.com and follow her on Instagram at @chanikasvetvilas

About Jennifer Cabral

Born in São Paulo, Brazil (1974), Lives in New Jersey, U.S. Photographer Jennifer Cabral holds a BFA from the School of Fine Arts Escola Guignard, and a BFA in Social Communications from PUC Minas, in Brazil. She is currently pursuing a MFA in Information at Rutgers University – School of Communication. Since 2010, she is a Library Collection Photographer at Princeton University reproducing books for it’s Digital Library. Cabral is currently pursuing a MFA in Information at Rutgers University – School of Communication. This is how Cabral describes her works: “My explorations in photography may be anchored in documentation and printmaking but it is the word that directs my art making. I frequently embed adjectives, nouns and verbs into photography as I search for understanding of my own feelings and experiences. Instead of capturing the external I recreate imagery and deconstruct sequences of events – am I recalling memories or my dreams? In my attempts to address issues such as climate change, immigration, racism or environmental crisis, what is revealed are my own histories. From universal themes personal layers emerge, and I become vulnerably revealed. My curiosity fluctuates among many themes as the collective accidentally collides into times and spaces I happen to occupy. Throughout these works, the camera has gradually become a secondary tool. As I resort to various archives to construct narratives, photographs become interwoven imagery so it can fully portray what I want to convey. From my wish to make my art relatable and accessible, digital iterations become freely available in hopes it will be spread in the winds of the web and carried away on devices so what was once mine can become someone else’s. Take it, if you wish.”

About Diane R. Wiener

Diane R. Wiener became Editor-in-Chief of Wordgathering in January 2020. Diane is the author of the full-length poetry collection, The Golem Verses (Nine Mile Press, 2018), the poetry chapbook, Flashes & Specks (Finishing Line Press, 2021), and the forthcoming poetry chapbook, The Golem Returns (swallow::tale press, 2022). Her poems also appear in Nine Mile Magazine, Wordgathering, Tammy, Queerly, The South Carolina Review, Welcome to the Resistance: Poetry as Protest, Diagrams Sketched on the Wind, Jason’s Connection, the Kalonopia Collective’s 2021 Disability Pride Anthology, and elsewhere. Diane’s creative nonfiction appears in Stone Canoe, Mollyhouse, The Abstract Elephant Magazine, and Pop the Culture Pill. Her flash fiction appears in Ordinary Madness; short fiction is published in A Coup of Owls. After serving as Guest Editor for Nine Mile Literary Magazine’s Fall 2019 Special Double Issue on Neurodivergent, Disability, Deaf, Mad, and Crip poetics, Diane was appointed as the magazine’s Assistant Editor. The Founding Director of the Syracuse University Disability Cultural Center (2011-2018), Diane now serves as a Research Professor and as the Associate Director of Interdisciplinary Programs and Outreach at the Burton Blatt Institute (Syracuse University College of Law); she also teaches in the Renée Crown University Honors program. Diane has published widely on disability, pedagogy, and empowerment, among other subjects. She is a proud Neuroqueer, Mad, Crip, Gender Nonconforming, Ashkenazic Jewish Hylozoist Nerd (etc.). Diane blogged for the Huffington Post between May 2016 and January 2018. You can visit Diane online at: https://dianerwiener.com.