This is Part II of an interview which took place in September 2021 after the exhibition Sutured Resilience closed at Artworks in Trenton, NJ. Sutured Resilience brought together artists Jennifer Cabral, Kat Cope, and Chanika Svetvilas, who explore trauma, memory, and empowerment to imagine a reality that finds strength in vulnerability through text, photography, sculpture, drawing, mixed media, video and participatory actions.

Diane R. Wiener interviewed Chanika Svetvilas and Jennifer Cabral for Wordgathering, via Zoom. This Zoom recording transcript was edited collaboratively by the three of us. Chanika Svetvilas is a previous contributor to Wordgathering (Spring 2021 issue), and introduced Jennifer Cabral and Kat Cope to the journal and Diane Wiener. (Kat Cope declined to be interviewed.)

Photographs courtesy of Jennifer Cabral, except final charcoal drawing—courtesy of Chanika Svetvilas.

WG: Right, it’s such a complicated and distressing thing to conceptualize. I’m also thinking about how many different ways each of you distinctly and in overlapping examples talked about care, just now, and the resplendent–I’ll use that word, a word of which i’m fond–the resplendent levels of care as a kind of brightness and as a form of engagement that is exceeding of but also because of the context. And so I was listening to each of you, of course, very closely and carefully and I was thinking about this framework or conceptualization that’s very practical, of mutual aid and of community creation and relationship, which comes up again, repeatedly, in the work you have done to describe but also the way you made the work available to each other and to other people. From the checking in during the beginning of interactions to how to make sure that people were, you know, protected as much as possible from risk and danger. And also the ways that artists can be with each other and with people who are maybe not artists, as well in a kind of community, in a digital environment. We’re not of course delighted by COVID, obviously, and yet there is a secondary gain and the innovative requirement to change the context in ways that were important to all of us. So I’m really struck by how many different ways you talked about care work. I have Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s book (Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice) sitting right next to me.

You know you’re describing art as care work in a way, and also you’re describing your relationships, as people who are also artists, as related to this creation of mutual aid and of care work and I think that’s really beautiful. I think sometimes we see how artists are stereotyped, sometimes, by people who don’t know what living in a world of creating art is like for each person, and there’s this idea that the art is the goal, the art itself. The product. But it’s certainly so much the work of artists (Crip and noncrip) to create communication because of the art. And the way you’re talking about mutuality and care and respect and the integrity of boundaries and the inevitability of doing that in an unavoidable nightmarish mess that is not affecting everyone equally at all.

So I was wondering if you have any thoughts about any of that mishmash of things I just said, you know, a lot of the labels, as some people call them. Again, I’m not making fun. I’m really not. But, “Oh well, this is really good, we should do this all the time,” some nondisabled folx have said. We know that Disabled people have been saying this all this time and now suddenly it’s a good idea, because you [nondisabled people] have to do it. And if that isn’t a comment on ableism, I’m not sure what it is. Of course, things should stay as accessible as possible, period. It shouldn’t take this.

So I don’t want to make a speech. If I already did, I’m sorry (!).

Would you like to share some more thoughts about mutual aid, care work, and your engagement with the arts in relationship? And the relationships to each other and the people engaging with the artwork, including that great example of people commenting on what resilience means. Maybe there are digital ways to do that too, of course, that would make that even differently available to people who maybe don’t write with a pen on a piece of brown paper wrapper (which is not a criticism–I’m just adding). So, any thoughts you have about that, beyond the ones you’ve already shared, which was so beautiful and profound? Thank you.

CS: Um, well in terms of our public programming, it is so important that processes be collaborative so, even if we have the intent of making it accessible, when you’re collaborating with an organization, they also have to be open to that too. So I hope that there is more awareness about taking action towards what accessible really means. And it also isn’t just about having the ASL interpreter, and the captions. What it’s really about is being open to all the different accessibility needs. And I could even go broader than that, like in terms of economic accessibility, for instance.

In terms of my art practice and how the digital space impacted my practice, I started an Instagram account during the pandemic. I didn’t have one before. And it was another way for me to connect with people, because New Jersey was under lockdown during the beginning of the pandemic. And so it was a way I could share my work and also get feedback. My art development was witnessed through Instagram. But then, on the other hand, when people who had the ability to actually visit our works in person and see Sutured Resilience, they were so surprised at what a difference it made to see things in person, because of the scale and just the materiality of the work.

So as much as it’s important to have other ways to access art like through a digital platform through Zoom, nothing can replace the in-person experience of art. I mean, I had an 18-foot drawing and you couldn’t show that on Zoom or a virtual gallery or on Instagram. And I had a six-foot revolving sculpture. That’s something you can’t have a sense of digitally within a small screen. So it’s challenging to want to find another way to show the work, but then being aware of its limitations. that it’s not necessarily interchangeable, and the digital space can’t replace the tactile materiality of the in-person scale of artwork. But it is making me think more about different ways information is received, and trying to be aware of how I can also make my work more accessible, when it is digital. Like, I’m still inconsistent with creating my image descriptions, and I haven’t created audio descriptions yet for my videos that are online through my website, so I’m aware of the lack of accessibility to my work I have online presently.

So I am thinking about what I can do and how much work I still have to do as well to make my work fully accessible. And I do think in terms of mutual aid and the three of us working together, Jen and Kat and I, it was also about really listening to each other, because as I said we had monthly Zoom calls, but there were times when someone would say, “this is too much screen time, I can’t do it,” or, “I can’t receive too many text messages, because it’s just overwhelming me,” so like really listening to what’s comfortable and pulling back and making sure that everyone’s choices were respected in terms of what their their needs were and that, as you said, it’s not goal-oriented, it’s process-oriented and not solely about we’re just wanting to meet this deadline, but what’s happening during that process and not just thinking about the show, but how we’re getting there. And it’s not just about filling a space, but how we’re going to create an experience to get there and do that respectfully.

WG: I love the way you said that. Create an experience together and do so respectfully. This process is a space, in a way that’s real. I thank you, for that’s one of those sentences I will have in my heart, probably for the rest of my life, so I really appreciate it.

Jennifer, did you want to add anything?

JC: About the issue of art as a product, and artists as part of a machine, a bigger process is that you have to fill in spaces and fulfill some requirements and meet some quotas, I think the whole process for me was shocking of how much I had to protect myself. It wasn’t something that was there, waiting. I had to put up a barrier. I had to create it and say, “I can’t do this.” It’s very hard to realize how many individuals in the arts live that way and create under such demands and pressure.

I think we as artists, just as human beings, should just remember that we are all delivering, presenting, creating, giving all that we are capable of doing in a moment in time. In the context of extreme uncertainty and constant change, we have to carve spaces in this changing landscape to care for ourselves. And if we are capable of doing that, there is a domino-effect of others having witnessed you claim such care for yourself.

WG: I’m extremely grateful to you for the wisdom that you just articulated so well and with such kindness and assertiveness. When we first started talking about doing this interview or having an interview–being in company, this way, I’ll say again–we knew and continue to know about the ways in which COVID has disproportionately harmed or endangered and been fatal to people from BIPOC LGBTQ+ Disabled communities. This is something you’re both, and I know Kat, are reflective about in the context of the work, and how the exhibit was shifted because of the context in which you found yourselves.

Is there anything else that you wanted to reflect on? And, I just want to thank you, again, for taking the time to be with me and with each other and have this conversation for Wordgathering.

CS: You brought up how resilience is an overused term that can be detrimental to communities as well, and when we came up with that title, Sutured Resilience, that was at the very, very beginning of the pandemic, in February [of 2020], and we were looking for a common thread.

And we thought about everything that we individually had gone through, and we thought the common thread was resilience, and then we felt like that was not the only defining factor, and Jen said, “what is that word when you stitch during surgeries?” and then we all said “sutures!”

And I think that the reason why it had to be Sutured Resilience was because it’s about the action, like it’s not like–and I hate the word overcoming–it’s not like you overcome something and it’s not an individual resilience, it’s about all the things that come into play to allow that resilience to happen. And in my 18-foot drawing, there’s a poem written on it, and one of the lines says, “I found sanctuary in kindness.”

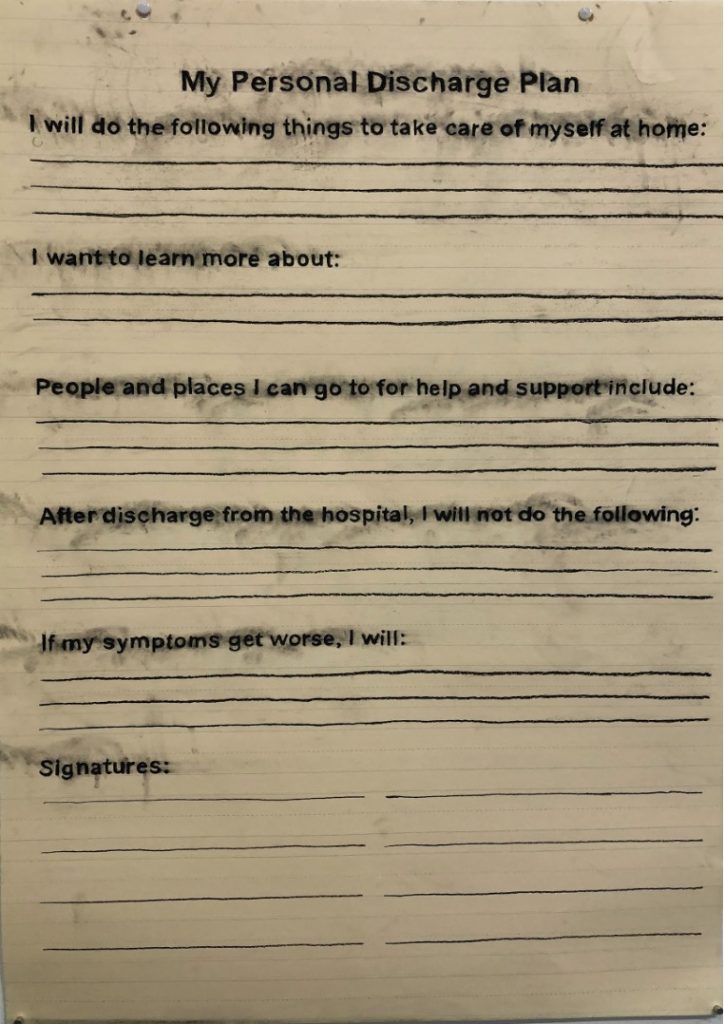

So, you can’t just be resilient by yourself. It is the community that supports you–its access to resources, its mutual aid, its understanding that you’re not alone and doing it yourself. One of the drawings I have in the show is called, “My Discharge Plan,” and it was a page torn out of my workbook that was given when I was hospitalized, and it said at the top of the page “my personal discharge plan,” but it had to be signed off by the whole treatment team and I thought it was really puzzling: how is this my “personal discharge plan” if it’s not personal or private? There were statements that start off with, “I will do this”; “I will do that,” and then I had to fill in the blank. And there was nothing about, like, how am I going to access resources, like a job, income, a home, medical care, pay for prescription meds. I was fortunate that I was able to navigate all that and access resources, but not everyone has that kind of privilege. So then resilience means different things to different people in different contexts.

WG: Yes, well, thank you for that, and I mean that that description is really vast and deep and one of the things that I’m affected by, and in listening to you, is the idea that sutures are threads. You mentioned things being threaded together and people being threaded to one another and interdependence and, you know, I’ve been thinking about all the different social media and interventions, some of which are not so easy to say politely. But some of them seem necessary, even if harmful in some ways, frankly. I think that the assertiveness that accompanies some of the anti-ablest work on social media has highlighted that the word resilience is not necessarily something people want to have to have an association with. It’s often because of having no choice, but to have to figure out how to be resilient in the world that is so oppressive to so many different communities who were marginalized and treated in an inequitable and violent way.

So the idea of suturing, in a purposeful intentional collaborative interdependent way with threads is…I’m not surprised that people were so responsive, in particular, to the art piece you’re describing.

I want to hear what you have to say about what we’re “on” topically now–as it were–Jennifer.

I’ll add that I’m really very intrigued by this metaphorization–one that pisses me off–about how the artist who is emotionally variant, you know…and people get really mad at me when I say that I’d rather that Van Gogh didn’t suffer, and we didn’t have any of that artwork, like it would have been okay for him to have been able to produce that artwork and not felt like shit all the time and had the terrible time that he had. In the ways that he existed and exists in the world, because of all the different things that are theorized about him that we don’t really even today totally don’t know what happened, and you know…but if his suffering could have been mitigated or disappeared, it would be okay with me not to have the sunflowers. It would be okay with me, like I don’t think artists should have to be expected to suffer to produce art or that people who are bipolar are better artists and closer to some deity. I think that’s bullshit.

I’d be very interested, maybe at another time, to talk about that together, because I think some of what you talked about with that particular art piece strongly index some of those debates, and that people maybe were partly affected so strongly by the wisdom of what you wrote and the wisdom of what you artfully presented in the visual form.

JC: My trauma is not where my art starts. It seeps through it, because it’s there. I can’t hide it. I can’t hide it, even if I wanted to, but I can make it become “the” thing, right?

WG: It seeps through…yes. All these different words, right, so the sutures, and the threading of communication, and the seeping of trauma, which of course happens with paint. I mean, it’s really…there are so many powerful physical images and emotional physical images and maybe thinking of our colleague, Margaret Price, you know, the body-mind images that refuse the Cartesian dualism. I’m very appreciative.

[Diane asks Chanika and Jennifer if they feel comfortable describing their contexts, for the sake of accessibility, in order to include the readers in the experience of the Zoom interview. Both agree enthusiastically.]

CS: Well I’m actually in my apartment in front of my bedroom door with white walls and directly behind me, which is a little hard to see in detail, is a smaller scale, is a nang yai, which is a Thai shadow puppet of an elephant with three guardians, which are called the yak in Thai on the elephant with sort of like filigree. It’s made from cow hide and then it’s painted. I actually studied shadow puppets many years ago, so this is made by one of the shadow puppet masters, Nang Suchart. And then two small wooden shelves with small books and a basket and a flowered vase and then a little lamp that was my dad’s. Then a small abstract photo image to my right.

WG: Thank you, thank you.

JC: And I’m in the attic of the house where I live with my husband and his family. This house is outside Princeton, in Lawrenceville, New Jersey. So my room is my art studio. It’s where everything happens. It’s where I am all the time, this tiny triangle, this attic. In the background there is the screensaver of my computer made of one of my collages. Collage for me, became like an internal calendar, markers of a shift in my interests, a shift of the seasons, a shift of my rhythms. I am called to create a collage when something shifts in me, another phase is starting to happen, maybe every three months I make a new one. This image in particular has the words “Circular Motion” in the center of this collage. It has images of a cowboy, an American flag and shelves in a supermarket, but at the center there is a powerful and beautiful Black woman who symbolizes for me a force moving this nation.

WG: Thank you. I felt like we needed to end with an imaging and that art was obviously going to be part of that, so I thank you.

[Diane is seated in her dining room in upstate NY, in front of a maroon wall with various brightly colored artwork shown in fragments, and under dim lights.]

Additional Resources

Return to Part I of this Interview

Back to Top of Page | Back to Interviews | Back to Volume 15, Issue 4 – Winter 2021

About Chanika Svetvilas

Chanika Svetvilas (she/her/hers) is an interdisciplinary artist based in Princeton, NJ who utilizes lived experience to create safe spaces, to disrupt stereotypes, and to reflect on contemporary issues. She has presented her interdisciplinary work at ABC NoRio, Brooklyn Public Library, Westbeth Gallery, Denver International Airport, Asian Arts Initiative, Islip Art Museum, Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning, Plainsboro Public Library, and conferences including the Society for Disability Studies, Pacific Rim International Conference on Disability and Diversity, and College Art Association, among other spaces and contexts. Her work is also included in Studying Disability Arts and Culture: An Introduction by Petra Kuppers and published in Wordgathering and Rogue Agent. She is the recipient of the New York State Arts Council’s Decentralization Grant and the Foundation for Contemporary Arts Emergency Grant. She holds an MFA in Interdisciplinary Arts from Goddard College. She is curator for the annual exhibition, Unique Minds: Creative Voices, at Princeton University and presented by the Graduate Student Government Mental Health Initiative. Svetvilas is also co-founder of ThaiLinks and Thai Takes, the first biennial Thai film festival in New York City. For more information, visit chanikasvetvilas.com and follow her on Instagram at @chanikasvetvilas

About Jennifer Cabral

Born in São Paulo, Brazil (1974), Lives in New Jersey, U.S. Photographer Jennifer Cabral holds a BFA from the School of Fine Arts Escola Guignard, and a BFA in Social Communications from PUC Minas, in Brazil. She is currently pursuing a MFA in Information at Rutgers University – School of Communication. Since 2010, she is a Library Collection Photographer at Princeton University reproducing books for it’s Digital Library. Cabral is currently pursuing a MFA in Information at Rutgers University – School of Communication. This is how Cabral describes her works: “My explorations in photography may be anchored in documentation and printmaking but it is the word that directs my art making. I frequently embed adjectives, nouns and verbs into photography as I search for understanding of my own feelings and experiences. Instead of capturing the external I recreate imagery and deconstruct sequences of events – am I recalling memories or my dreams? In my attempts to address issues such as climate change, immigration, racism or environmental crisis, what is revealed are my own histories. From universal themes personal layers emerge, and I become vulnerably revealed. My curiosity fluctuates among many themes as the collective accidentally collides into times and spaces I happen to occupy. Throughout these works, the camera has gradually become a secondary tool. As I resort to various archives to construct narratives, photographs become interwoven imagery so it can fully portray what I want to convey. From my wish to make my art relatable and accessible, digital iterations become freely available in hopes it will be spread in the winds of the web and carried away on devices so what was once mine can become someone else’s. Take it, if you wish.”

About Diane R. Wiener

Diane R. Wiener became Editor-in-Chief of Wordgathering in January 2020. Diane is the author of the full-length poetry collection, The Golem Verses (Nine Mile Press, 2018), the poetry chapbook, Flashes & Specks (Finishing Line Press, 2021), and the forthcoming poetry chapbook, The Golem Returns (swallow::tale press, 2022). Her poems also appear in Nine Mile Magazine, Wordgathering, Tammy, Queerly, The South Carolina Review, Welcome to the Resistance: Poetry as Protest, Diagrams Sketched on the Wind, Jason’s Connection, the Kalonopia Collective’s 2021 Disability Pride Anthology, and elsewhere. Diane’s creative nonfiction appears in Stone Canoe, Mollyhouse, The Abstract Elephant Magazine, and Pop the Culture Pill. Her flash fiction appears in Ordinary Madness; short fiction is published in A Coup of Owls. After serving as Guest Editor for Nine Mile Literary Magazine’s Fall 2019 Special Double Issue on Neurodivergent, Disability, Deaf, Mad, and Crip poetics, Diane was appointed as the magazine’s Assistant Editor. The Founding Director of the Syracuse University Disability Cultural Center (2011-2018), Diane now serves as a Research Professor and as the Associate Director of Interdisciplinary Programs and Outreach at the Burton Blatt Institute (Syracuse University College of Law); she also teaches in the Renée Crown University Honors program. Diane has published widely on disability, pedagogy, and empowerment, among other subjects. She is a proud Neuroqueer, Mad, Crip, Gender Nonconforming, Ashkenazic Jewish Hylozoist Nerd (etc.). Diane blogged for the Huffington Post between May 2016 and January 2018. You can visit Diane online at: https://dianerwiener.com.