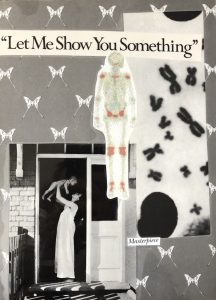

Let Me Show You Something: Disability History and Eugenics Disguised

Let Me Show You Something combines a collage, short poems, and vignettes about my experience as a STEM student whose autistic identity is often medicalized. My objective is to critique the overmedicalization of disability identity and shed light on the reality of many disabled healthcare workers’ internal battles within the system. I begin reflecting on my experiences in a karyotyping activity in high school biology class, and weave in various experiences with ableism as a student nurse, ending on how I approach the surveillance of my autistic traits in my current clinical rotations. Part of my disability identity development in young adulthood has been learning disability history, including the painful historical mistreatment of people with disabilities in healthcare institutions. While I am optimistic about the progression of anti-ableist health sciences education, knowing of the past highlights present issues in alarming ways.

Content Warning: This multimedia project discusses themes of ableism in medical and academic contexts, genetic testing, institutionalization, and the exploitation and medicalization of autistic people.

I remember sitting in the combination desk chair of a high school biology class, completing a karyotyping activity. Karyotyping is a type of genetic testing that visualizes a set of chromosomes. My assignment was to cut out chromosomes from a piece of paper and match them to a model karyotype, searching for differences. In a real karyotype, cytogeneticists scout for unexpected results, indicating genetic disability. Many will refer back to these results – too much, too little, wrong place, wrong time. This may be the best time in history to be disabled, somehow.

Gene Puzzle – age 14

Inversion of expectations.

Duplication of forgotten

ancestors locked away.

Deletion of the opportunity

of experience.

Insertion of hate.

Translocate our futures

into nothingness.

Fidgeting and rhythmic tapping cradle my attention, beams focus onto the karyotyping assignment. There is a way one is supposed to sit in academic and professional environments – still. I never quite accomplished this act. It was there, in biology class, that I finally felt smart enough to apply to nursing school. In this particular classroom, there was no authoritative questioning of my accommodations, and my queries were answered with each frequent raise of my hand. But then, always, there were the lingering reminders of a cleaved identity. Scientific education, now health education, has been like this, comforting and confronting. No grade, award, or scholarship is heavier than the cultural notion of “the fixers” and “those needing fixing.”

Secret Way – Age 14

I’ll stay, to make it somewhere I belong.

My teacher never spoke to me about it.

She called my mom – “Something is wrong.”

It is not too late in the day.

We have decided to give you 12 more hours.

Who am I to use your time?

When we are young and assumed to be full of energy, our movements are less surveilled. With age and continuous time in clinical rotations, peers learn what to look out for. Mentors speak their observations. The charting prompts are, as I feared, mapped from their minds onto their perception of me. My ID badge calls me a student. One day in a nursing clinical rotation, my nurse mentor observed my stims. She called me out as if to warn me of what I look like – who. Earlier, she had applauded my connection with our psychiatric patients. These are two symptoms of what our field labels a disorder.

Charted – age 20

“You seem particularly wound up.”

Just the other day, a man post-op, post-wars.

Same medication and dose as mine, pill, and cup.

Slightly senior, SSI, kept here indoors.

He was dying.

Upstream, he was held beneath the water,

Forced to drown for years.

There is barely time for a quick cry over his slow death.

Vitals are due.

Once the karyotyping process is complete, and the results are interpreted by a geneticist, a genetic counselor explains the diagnosis to the parents of the fetus. Down Syndrome, Patau Syndrome, Edward’s Syndrome, Turner Syndrome, and more are all identified by this test. In elementary school, I realized that as I grew older, some of my classmates seemed to disappear. Into classrooms with small windows and lots of adults, but few other children, they went. To the basement, led by held hands, they were taken. I’d always been told my school district was a sort of “beacon of public school light” for “special-needs” families. I remember reading, as I prepared to graduate, that my school district had the fifth-highest seclusion and restraint statistics of any district in the state.

This is one of the more severe and noticeable forms of segregation. As I progress, each step further into understanding education, civic engagement, healthcare, legal processes, and more, I continuously realize all the private hallways disabled people are led down, away from full participation in society.

Excavating Expectation – each age

I hunger for that place

To decide it, myself

Dug up from whatever rumbling buried layer they’ll call

my own.

In high school, movement, speech, expressions, and other behaviors grew increasingly standardized. In my Advanced Placement classes, I created my script to explain that my accommodations were, actually, necessary. STEM classes were the most difficult places to get access. Tests were taken in backrooms and before school even started, and I felt that was progress. I only saw these segregated, though once present peers occasionally, leaving a class a few minutes before passing time, before the swarms of students packed the hallways.

Again, in my biology classroom, I swiveled my scissors around the curved chromosomes that were scatter-printed across the page. Bits of blank paper flew to the floor – discarded in the recycling, stuck to students’ shoes, forgotten, and tracked outside to the parking lot. We are supposed to feel satisfied because at least these scraps are going to the recycling, not the trash. Before I connected with the disability community and learned from my elders, I assumed institutionalization was behind us. Eager students wondered which of the three papers – which bodymind – we had each been given. I followed the directions in matching them, measuring against conformity, the first thing we were taught. It may be the most violently enforced lesson. You are told that to be loved, you must commit this act of conformity. I spent a few pressurized moments searching for a chromosome I thought may have fallen to the floor.

Vitals – age 13

Free local ASL course

The mothers, Deaf babies, and me

Generationally resisting audism, spinning force

If it has never been there, do not mark it absent

Why mourn what never was?

A celebration in each phalangeal movement

The “missing” sex chromosome indicated Turner syndrome. My fingers were frosted with Elmer’s glue residue after I adhered the butterfly-shaped chromosomes to the paper. I peeled the film and examined the fingerprints left behind. We read a brief list of characteristics of each diagnosis from the board. Black and white pictures, past, of children propped and posed, staring. Weakness, problem, difficulty, and susceptibility are words often used in health education to describe the people who are home to these chromosomes. That was it, the class as I remember it. They moved on to the next topic.

I will remember this memory – viewing the disabled children connected to the investigated karyotypes on the big screen at the front of the room, revisiting me in college. During the lecture where autistic people were covered as a population for the first time, tears welled in my eyes. My throat burned as I felt an existential weight to the hateful words. Again, during one of the only other times autism was represented in the curriculum, I recalled the screen in my biology class. Modern snapshots. No more posing, just heads hitting the walls, toddlers wailing, broadcasted meltdowns, and parents speaking shame straight into their children’s faces on video. I cannot move, but each classmate who turns to look at me is registered.

I am told, “You should consider a different career.” The door to the nearest private hallway swings open. I move past it, into the arms of the other disabled nursing students at my school. We don’t mourn ourselves. Instead, our tears gather over having watched our peers consume this hateful rhetoric. We regroup, walk through the woods on our campus, and imagine how different it could all be.

Protest and Survive – age 12

On the day I knew myself

Introduced with apology

Dissonance, the all-knowing mirror cracked by the weight of that book

Her lips, spat, into my lap, Pathology

Relief in a first full look

This word of me

Secret joy, I enveloped myself in the song of maternal tears

Do Not Be Sorry

I went home from high school biology class that day with a new idea, a possible path blossoming in my mind. How wonderful it must be, to be introduced, shake hands and greet a part of your future child, with a clinician who doesn’t apologize for their potential existence? What power, in communicating your emotions, as a healthcare worker, do you cast upon someone’s framing of their own life? I told my mom that I wanted to be a genetic counselor. She explained to me something I had not considered, the selective medical deletion of disabled people under the guise of societal advancement. The puzzle collage I had created in my fifth hour that day had implications beyond paper scraps on the floor and an “A” for completion in the grade book. She would tell me, as a mother, that the weight of judgment is heavy upon each creator. The karyotype was not an apology, not an invitation to greet someone in all their detailed wonder, but perhaps a critical investigation of worth.

Whether we name it or not, there are layers of intention in all lessons. Knowledge, to prepare a world for your child, can be the intention. Knowledge, to prevent the world from having to change, can be the intention. Schoolkids are still completing open-ended karyotyping activities, gasping and exclaiming at whichever (or whoever) – often referred to as whatever “surprise” their assigned paper revealed. Kids like me, for whom order, repetitive processes, puzzles, and cataloging are comforting, sit in uniform chairs arranging constellations of potential energy without knowing if it will shoot into the air of life or fall hard into the ground. College students in health-science programs, who are like me, are learning about their communities from a lens that others them, in a lethal way.

Yearning Place – age 21

Teach me

to handle each possibility with sacred care.

Healthcare and technology have the potential to advance disability justice or erase disabled people from the face of the Earth. Each time I see a chromosome in my textbooks, one thought recurs: there are only one to two people born with Down Syndrome each year in Iceland (Quinones and Lajka, 2017). To participate in healthcare education and practice, as a disabled person, is teeming with many great nuances. To lend myself to institutions that dance with our (disability community members’) existence flippantly, but who also grant me the experiences to learn my value through disability studies and disability justice scholarship, is labyrinthine. Though I do not have a condition that is identified through karyotyping, there are significant genomic research efforts to identify what exactly makes people like me, genetically. I find myself checking the schools that host graduate programs of interest, finding they too, are genetically coding the spit donations I am constantly being advertised. What is often called “cutting edge” research boils down to something existential, an ability to prevent disabled people from the chance to ever breathe the same air as nondisabled people. How offended some academic peers are, to find out I am there, accommodated, diagnosed, and talking openly about this lens I exist through. To them, there is no world in which I am who I say I am while staying afloat in their waters. I hold on tight to the helm when storms are raised against the radical idea that we are worthy of full lives.

Heumann, Berne, Mingus, Milbern, Wong – age 21

I must believe

All borders of hate Are Weak.

I must make words

to remove the loose bricks.

For the sliver I snuck through

was created this very way.

When these medical advancements are taught without the input of the communities they affect most, the ethical considerations are not in the periphery of the learners, they are out of view. The same tools used to build a home can kill the person who lives inside of it. Without explicit disclosure of perspectives from other fields, such as humanities or disability studies, but most importantly, the community of people being researched, science led by dominant social groups can bulldoze through identities, robbing us of existence.

While creating this piece, the arguments often used to justify the research that feeds the ever-turning wheel of velvet eugenics came to mind. Ensuring parents, and whole communities, are promised a “normal” child who will live up to expectations prescribed for and by nondisabled people is regarded as more important than the survival of diverse disability identities. I thought about the old black and white photos used to show institutionalized people. They always seem to be black and white – of the past, as if there is not a whole other disabled nation within U.S. borders that is walled off from society. I can assure you that their screams are audible, though you are not hearing them.

I remember the glue between the valleys of my fingerprints had hardened as I stared at the butterflies – so neatly arranged on the collage. Unnaturally arranged, artificial placements. Designer. I rubbed my fingers together and as the glue fell to the ground – rolled like dead skin. The vivid picture of autistic hands, desperate to move, being glued down to a table in autistic rights activist Julia Bascom’s “Loud Hands” essay flashed across my mind. Reading this essay at age 19 created a defiance that has slammed the doors of numerous hallways that attempt to lead me out of believing I can be a valuable nurse, researcher, educator, and advocate. I thought about the masterpiece that codes each of our embodiments. A soul is home to these chromosomes too. Knowledge is power, but power can be abused to such ends that it wipes out an entire people.

Picky Eater – age 20

Slip into the doors of my clinical rotation

Drive past the ABA clinic with my college’s name on it

Stare into nonreactions to Judge Rotenberg

Hold the curriculum that stigmatizes my own being

in my mouth

for these 8 hours.

Absorb the values of care and compassion

and spit the ableist poison

down the drain

at the bus stop on my way

home.

This piece originally appeared in a slightly different and earlier form in the Disability Network Washtenaw Monroe Livingston’s disability pride exhibition.

Find more Art published in this issue of Wordgathering.

Back to Top of Page | Back to Manifestos | Back to Volume 18, Issue 2 – Winter 2024-2025

About the Author

Tess Carichner is a nursing student minoring in disability studies and global health at the University of Michigan. She is the leader of Disability Justice @ Michigan and a research assistant in the Digital Accessible Futures Lab. Her work revolves around disability culture, the interactions of disabled individuals with ableist institutions, anatomical imagery, and surrealist autofiction. As the editor of Accessing Disability Culture, she values multimodal arts and collective creations.