“Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer”: On Curating an International Intersectional Queer/Disability Exhibit in Berlin, A Conversation between Kenny Fries and Kate Brehme

“Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer,” the first international exhibit on queer/disability history, activism, and culture, opened at the Schwules Museum Berlin on September 1, 2022, and will be extended to run through at least April 30, 2023. Wordgathering asked curators Kenny Fries and Kate Brehme to talk about important aspects of curating a queer/disability exhibit to document the process of the exhibit from a disability perspective. “Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer,” has been described by Art Agenda as “groundbreaking,” and Frieze magazine points out the exhibit uses “queer and crip experience as the starting point for a wider transformation of aesthetic norms.”

The exhibit includes the work of over 20 contemporary international artists whose works speak to the historical themes and objects of the exhibit and includes a selection of work by artists who created while institutionalized and whose works were collected by the Prinzhorn Collection in Heidelberg, as well as a section on important queer/disabled artist icons Lorenza Böttner, Raimund Hoghe, and Audre Lorde.

With an audio guide; a German Sign Language video guide; texts in German, English, and in German easy language; tactile models; a tactile floor guidance system; transcriptions of audio works; and German and English subtitles of video works, the exhibition enables all visitors to experience the exhibition as accessibly as possible. The Schwules Museum will use the barrier-free museum entrance for all visitors starting with the opening of “Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer.” For those who are unable to physically access the museum there is an extended accessible exhibit website and a captioned (both in English and German) curatorial video tour.

Kate Brehme: Perhaps to start you can talk a bit about how the idea for “Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer” began.

Kenny Fries: The exhibit began, over seven years ago, after I had briefly critiqued the physical access issues and severe lack of disability representation in the big Homosexuality_ies exhibit at the Deutsches Historiches Museum and Schwules Museum in Berlin. Birgit Bosold, a curator of that exhibit, and member of the Board of Directors of the Schwules Museum, approached me after my critique, and through our conversation “Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer” was born, with Birgit as co-curator. When funding was finally procured, we asked you, an independent curator and co-founder of Berlinklusion, a network for accessibility in art and culture, to curate the exhibit with us.

KB: I was thrilled when you and Birgit asked me to join the curatorial team.

KF: Has curating this exhibit been different from curating other exhibits, vis-à-vis access and other curation?

KB: Yes. While access has always been part of the creative and curatorial process in my exhibitions, working as an independent curator in smaller project spaces has often meant having to think through and create access measures myself, often with little resources. The fact that there was an existing institutional infrastructure, a team and even some existing access resources such as an existing relationship with members of the Deaf community made a big difference in sharing the workload. We also had quite a juicy budget for access, which definitely helped set this exhibition apart from others that I’ve curated. It meant being able to be a little more creative in terms of approaching access, for example, commissioning Quiplash to create an audio guide description of an artwork, as an artwork in and of itself.

KF: Having your expertise in accessibility was instrumental in access being fundamental to both the design and content of the exhibit. Access-wise, what most impressed me was 1) how when I visit the exhibit in my wheelchair, everything is at my height. I don’t have to strain in trying to read texts that are usually placed so high on the wall. And 2) when the floor guide system was installed, how it brought together the other design elements, completing the exhibit design. Both of these access features were intrinsic in not only creating a welcoming space for disabled visitors but also showing how such features can actually enhance an exhibit design. Access should not be an afterthought. Access can easily be organic to an exhibit.

You bring up having a “juicy budget” for access, which brings up how funders don’t understand how access can eat into a project’s budget. For example, if a project doesn’t receive all requested funding in a grant proposal, then much needs to be sacrificed because access costs remain pretty much the same no matter how large or small a project budget is. In this regard, the Canada Council for the Arts, when it funds disabled artists, offers access support for the disabled artist’s needs in addition to the usual grant amount. This is an important model, which I hope other funders will begin to use.

What do you see as the important issues brought to both the public and museums by the exhibit (in both content and access)?

KB: It was shocking to me upon hearing that our exhibition was unique in that it brought together the histories of queer and disabled people together for the first time in Germany, if not internationally. I think one of the most important issues is that museums need to start to approach storytelling from a more intersectional perspective, one that sees human experiences as intersectional and complex. The exhibition raises important questions about the establishment of art history and how and who it (mis)represents and proves, I think, that you can absolutely think through access in a playful, creative, and aesthetically pleasing way. Especially when the team curating the show is disabled/queer!

KF: Though I was the only queer/disabled member of the curatorial team, having a curatorial team that was either queer or disabled was crucial. And having you as the other disabled team member was incredibly important because, through your professional and personal experience, you intimately knew the issues we encountered along the way vis-à-vis presenting work of disabled artists. I’m more than tired of being the only disabled person in the room. In putting the exhibit together, we embodied the mantra “nothing about us without us.” Similarly, as disability studies scholar Carrie Sandahl (who coined the phrase we use as the exhibit’s title, in her article “Queering the Crip, or Cripping the Queer”) writes, “Those who claim both identities may be best positioned to illuminate their connections, to pinpoint where queerness and ‘cripdom’ intersect, separate and coincide.”

KB: In this way, our guiding principle for the contemporary art we chose for the exhibit was how it related to the various historical aspects of the exhibit, and the overall exhibit theme of “the ideal body.” This is not an “art for art’s sake” exhibit.

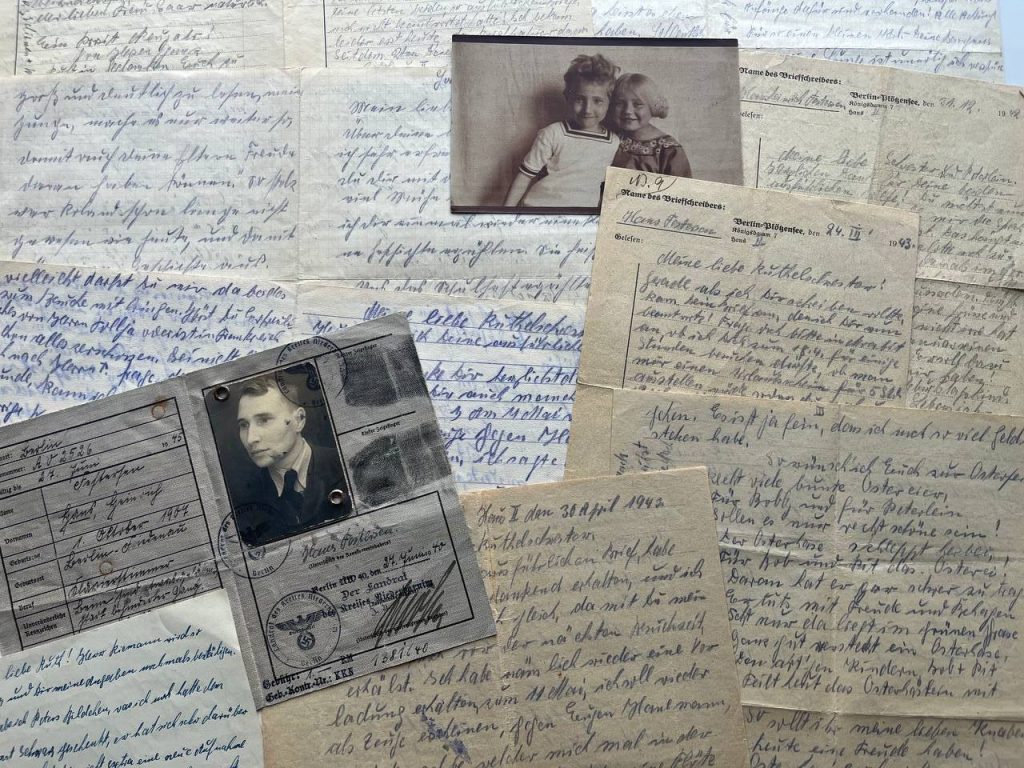

KF: And history shares the core of the exhibit. Perhaps the exhibit’s most resonant history relating to queer/disability intersectionality is the story of Hans Heinrich Festersen, who was hanged by the Nazis in September 1943. The difficulty in unpacking why Festersen was killed speaks to the challenges of living a queer/disabled life.

Do you have a story that sticks out for you from curating the exhibit?

KB: There are so many! Seeing the show all finished, being able to touch the tactile objects or listen to the audioguide, or the works we commissioned by Rita Mazza, Quiplash, and Riva Lehrer for the first time was so exciting! I felt incredibly privileged to have been in the position to give these artists carte blanche to respond to the theme of the exhibition, and to make space for their voices.

Find selected imagery from “Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer” in this issue of Wordgathering.

Back to Top of Page | Back to Interviews | Back to Volume 16, Issue 4 – Winter 2022

About Kate Brehme

Kate Brehme is an independent curator and arts educator with a disability, who is based in Berlin. Kate trained as an artist and in museum studies, and completed her doctorate at the Center for Metropolitan Studies at Berlin’s Technical University where she undertook research into the contemporary art biennial and urban space. Kate has worked in Australia, Scotland, and Germany on a variety of independent projects, exhibitions and events, and as an arts educator for organizations such as The Fruitmarket Gallery in Edinburgh and The National Galleries of Scotland. In 2017, Kate co-founded Berlinklusion, Berlin’s Network for Accessibility in Art and Culture, a collective of artists and arts mediators with and without disabilities who create inclusive arts projects and provide communities and arts organizations with advice on accessibility.

About Kenny Fries

Kenny Fries is the author of In the Province of the Gods (Creative Capital Literature Award), The History of My Shoes and the Evolution of Darwin’s Theory (Outstanding Book Award, Gustavus Myers Center for the Study of Bigotry and Human Rights); and Body, Remember: A Memoir. He edited Staring Back: The Disability Experience from the Inside Out. His books of poems include In the Gardens of Japan, Desert Walking, and Anesthesia. Twice a Fulbright Scholar (Japan and Germany), he was a Rockefeller Foundation Arts and Literary Arts Fellow, a Creative Arts Fellow of the Japan/US Friendship Commission and National Endowment for the Arts, and a Cultural Vistas/Heinrich Böll Foundation DAICOR Fellow in diverse and inclusive transatlantic public remembrance. His current work-in-progress is Stumbling over History: Disability and the Holocaust, excerpts of which have appeared in The New York Times, The Believer, and Craft, as well as form the basis for his video series What Happened Here in the Summer of 1940? He is a 2022 Ford Foundation/Mellon Foundation Disability Futures Fellow.