Performance. Disability. Art.: Public Celebrations of Love, Creativity, and Disability

(listen to the selection, read by Diane R. Wiener)

In 2013, I began developing a new artistic collective focused on the art of disabled people of colour, with my collaborator Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha. We had both been practicing artists for decades, Leah as a writer and performer, and I as a visual artist. We both had experiences of disability, and importantly, of disability communities in both Toronto and Oakland, California. We knew the ways that these community spaces could create opportunities for visibility and liberation but also the ways that mainstream disability communities centered whiteness and thus generated a sense of erasure for sick and disabled people of colour.

Together, we wanted to create something new—an arts collective that focused on the contemporary production of racialized disabled people—in ways that were supportive and embracing of “crip ways of working.” We wanted to be able to make our own new work, support others making work, and showcase everything in a high quality beautiful way, but on our own timelines and in ways that respected our bodies, our minds, our limitations and our ways of working. We wanted to build community and to come together to share and unify our shared experiences as disabled artists of colour.

This pushed against the individualizing nature of disability in an ableist society. Coupled with the isolating effects of disability, maintaining an individual artistic practice can be a very isolating experience. Often, artists go off and produce work alone, we are encouraged to work in silos, producing “great work” that was somehow divorced from a sense of community—the product of a “solitary genius” rather than growing out of years of social inquiries that were intimately connected to others and the world. In contrast, Leah and I wanted to challenge the marginalization felt by many sick and disabled, queer and trans people of colour (QTPOC) within white disability spaces including within disability arts zones. We wanted to centralize experiences of difference, creating a sense of collaboration and unity.

We decided to name our group PDA: Performance. Disability. Art. PDA reflected our areas of work, performance and art, literally centering disability in our frame. But it also playfully employed the acronym PDA, which in common parlance is used to refer to “public displays of affection.” Our work was to be one of love, of affection, and of celebration in a public sphere. PDA would “create spaces, places, events, as well as unstructured moments of being together” that celebrated sick and disabled QTPOC communities, interrupting the normative space of the arts, of performance, and of white disability community.

PDA grew out of our experiences as racialized artists who engaged with disability in our work. Leah had co-founded Mangos With Chili, a touring queer and trans people of color cabaret and had co-founded Toronto’s Asian Arts Freedom School. At the time, when we began discussing PDA, they had been working as a lead artist with the disability justice incubator Sins Invalid in California and were interested in thinking about mad, crip, sick and disabled artistic production in Canada. I had been actively engaged with disability arts in Canada, often as a critic of the lack of diversity within the field. I had participated in the jury for the first Canadian Council Disability Arts Grant competition in 2012. I presented at the first-ever conference on museum accessibility, Connections, Collections and Communities: Making Canada’s Museums Inclusive and Accessible, which took place at National Gallery of Canada, in Ottawa, in 2009, considering the needs of racialized artists with disabilities in the museum sector. I had also helped Blockorama, the black queer and trans arts festival at Pride in Toronto, with which I had been volunteering for 12 years, become the first stage at Pride to actively feature disabled and Deaf performers, to have ASL interpretation, and to take place on a fully accessible stage.

We came together to consider what was happening in Canada, and to think about what we needed and wanted as racialized queer and trans artists. We were interested in creating a space to celebrate the work of disabled artists working across performance, theatre, and visual art mediums that could act as an art incubator and supportive production resource simultaneously. PDA would become a space where we could invent a cripped, racialized language within disability arts. We wanted to develop a process and way of working that would be rooted in cultural communities and in activism. We wanted to develop a process and a sense of time and timeline that embraced neurodiversity and that attempted to avoid an overzealous production schedule. While we embraced multiple artistic mediums through our work, performance featured heavily in our imaginings of this new collaborative space.

We wanted to explore the space created through performance to create unexpected encounters that highlighted the instability of the fix on the nature of disability; namely the fix on disability arts that centralized white disabled experiences as the essence of disability arts. Our work would help destabilize these assumptions, through a celebration of art-making from the margins of the margins.

Cripping Your World

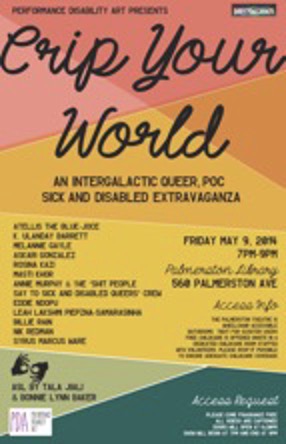

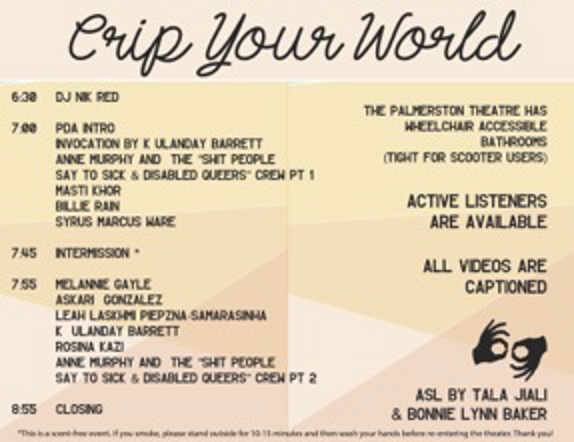

Our first public project was presented as part of the 29th Mayworks Festival in 20141. We co-curated an evening cabaret-style event called “Crip Your World: An Intergalactic 2QT/POC2 Sick and Disabled Extravaganza” featuring the work of k. ulanday barrett, Mel Monoceros, Askari Gonzalez, Rosina Kazi, Masti Khor, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Billie Rain, Nik Redman, and Syrus Marcus Ware. Our project description (2014) read as follows:

Crip your world! In this amazing performance experience, disabled, sick, Deaf and crazy queer and/ or 2POC artists will take you on a journey into our bodies’ genius. Get ready to be transformed by our sexy, complicated, life saving, deeply needed stories. Come experience the sacred, divine, and revolutionary nature of disability and see some performance that will blow your mind and heart and give you all the disability justice genius you didn’t know you needed.

The evening featured video work about being trans, disabled, and of colour, a humorous send up of the “Shit people say” meme about sick and disabled queers3, performances, audio soundscapes with full captioning, comedy, music, singing, spoken word, and installation art.

We provided child care for anyone who wanted or needed to come with their kids. There was much effort put into making the space scent-free, including working with the theatre to use unscented natural cleaners for one full week before the event, and working with the potential audience on strategies for coming scent-free, and for handling other needs like smoking, in ways that were keeping within these goals.

All audio was captioned, and we had two American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters from queer and trans communities. There were verbal descriptions of all visuals. Recognizing the significance of online spaces as gathering places and resources for many sick and disabled folks and the need to have a way for folks to be part of the event from their homes or spaces not inside the venue hall, we created a livestream feed that broadcast the entire program in real time. This event was unique in so many ways because of its framing: as a celebratory moment to showcase the creative brilliance of sick and disabled racialized queer and trans folks, and because of the accessibility of the event. One online attendee stated, “very appreciative for your work in making the live stream happen! and all around, thank you—caught myself being, like, is all of this really happening?” (personal communication, 2014). This quote illustrates the need for gatherings such as Crip Your World.

And it highlight’s Eliza Chandler’s 2013 assertion that “Enacting crip community by creating spaces, places, events…reveals just how inaccessible, inhospitable, and even dangerous the ‘normative terrain’ is.”

Remembrance, Space, and Time

The work that I created for Crip Your World directly addressed memory, culture, and community. I created a performance work entitled, “Do You Remember Me?” which incorporated humour, music, dance and story-telling to address the prioritizing of the ability to remember. This insistence is built into our work and social life—to be able to recall names, places, events, and, in my work field specifically, the names of artistic periods, artists, and obscure galleries around the world.

I stood in front of the audience and drew on stories from my life, of social interactions gone wrong when disability appeared through expectations of remembering. I explained,

It’s that look, the bright face, eyebrows raised, openness, enthusiasm…the familiarity of seeing someone you know, the recognition written across their face…And this sentiment, that specific expression on the face that says recognition—this expression sends cold waves of shock and fear down my torso. Because I have no idea who this person is. Not a clue! They could be my roommate, my co-worker, my cousin… I won’t recognize their face, I won’t remember their name….

I continued, telling stories about the experience of moving through the world with a brain that cannot recall important memories, explaining my use of anti-psychotic medications in the 90s, and their resulting effects. I chose to tell this story with humour; the real story is much less funny. My experience with anti-psychotic medication in 1997 has left me with a six-month gap in my history—time that I may never get back. It has resulted in countless incidents4 where remembering could have saved me much embarrassment, but where remembering was impossible for me.

Yet, in this performance, I embraced my brain, my memory, my life for what it was. I asked myself, was my brain the issue? Or was the issue more that we insist on prioritizing those who can recall names, dates, data, on command? What could the world be like if we could all say, “Um, I don’t actually remember.” I imagined this and felt free. And so I stated clearly to the audience,

I think that we put way too much pressure on ourselves to remember things. We celebrate remembering as if it was the most important thing. I disagree. And so, I have created a short audience call and response project that will help us to get over this drive to remember. When I ask you to, can you please yell out NO with me?

#2 Color photograph of the opening of Crip Your World. A dark stage with four people standing in front of a blank white screen. On the left is a person adjacent to a microphone who is gesturing with their arms, facing three others to the right on stage who are holding posters with the word NO in large red letters.

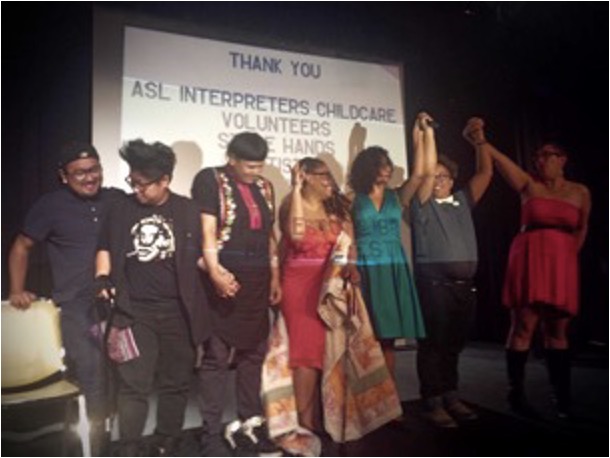

I proceeded to play excerpts from songs with the word or concept of “remembering” as central to the thesis. I brought our fellow sick and disabled QTPOCs to dance and wave giant signs that read “NO” every time they heard the word “remember.” I encouraged the audience to yell out “NO,” as well.

This playful employment of call and response challenges traditional comedic tropes (as in the often trite, “where’s everybody from?” comedic one-liners that serve to differentiate the audience from the performer rather than co-creating space together) and draws on my own family history. As the great-grandchild of enslaved people working on slave labour camps in Mississippi and Tennessee, call and response has been passed down to me as a way of connecting people and holding space together. As Fred Moten (2003) explains,

Having been called by call and response back to music, let’s prepare our descent: let the call of call and response, passionate utterance and response […] that open the way into the knowledge of slavery and the knowledge of freedom—operate as a kind of anacrusis (a note or beat or musicked word improvised through the opposition of speech and writing before the definition of rhythm and melody).

This opening, or liminal space created when we all cried out NO through call and response, allowed me to connect intergenerational memories of containment, enslavement, and of resistance to my present, while illustrating the ways that the medicalization of disability impacted my access to memory. We were collectively resisting the colonial insistence on remembrance, while also remembering Mad justice and times of resistance in a sanist world. The performance thus played with time—past/present, separation/togetherness—the performer and audience joining as one in moments of the performance, and the notion of disability as public/private; we engaged the confessional nature of exposing my experiences to an audience of peers, many of whom I had trouble “remembering” from one interaction to the next. The piece aimed to open a dialogue about the social expectations that we place upon each other, even within marginalized activist communities fighting for social change.

My employment of narrative storylines, music by artists of colour, and audience participation that challenged ableist notions of brain function cripped (and coloured?) the medium of comedic performance, creating “a disability style” of communication that was rooted in my positionality as a black disabled trans performer. In my performance, the humorous excerpts that highlighted my public experience of memory offered one level of understanding, poling above the soil and shining in the light. Below the soil, my story is allowed to breathe and exist, with all of its painful and complicated history of medical interventions, of medical violences that have had a lasting effect on my ability to hold on to the fabric of my life—my memories.

The performance was well-received and many came up to me afterwards to share similar stories, to offer solidarity, and to re/introduce themselves to me, addressing my request for this in the performance. My performance weaved remembering and forgetting together with time, gesturing at the future. It had a lasting impact on my social interactions with the audience for years to come. People still come up to me and introduce themselves, saying that they remembered this from my performance. In this way, it reframes my experience, shifting it away from being a “problem” (Titchkosky, 2012) and instead celebrates its difference. Through the simple act of changing initial social interactions to include a reintroduction, my mind is honoured, and existing social interactions that require compulsory retention of swaths of information are put on display as a “problem.”

I Feel Disabled

Following our performances, we packed up the theatre and began the process of returning to our homes. Although the space was accessible, with an elevator leading to the ground level, the elevator required a key to operate. During our show, we had had volunteers stationed at the elevator; we were insistent that no one have to wait to use the elevator by having to search for the key. However, after the house lights went up, and the audience and volunteers cleared out, only our take-down crew remained: Leah, myself, and two of our performers, Mel Monoceros and our DJ, Nik Redman—and our stage manager, Aemilius Ramirez.

After a long night of performance, our bodies and minds were tired. We all needed the elevator to leave the space, but the building staff had left the venue with the key. We talked amongst ourselves and figured out which of us had enough spoons to go and find the staff member with the key. Once we had decided, those of us who remained waited by the elevator, tired and longing to sit down. One of the performers turned to me and said, “I feel disabled.” I was struck by this sentence. This simple phrasing highlighted what we had created together that night: a space to celebrate and explore disability together, to feel powerful and to feel that our experiences of difference were amazing, even special. This was made apparent in this moment where the opposite was occurring. We did not feel powerful and free, we felt alone and literally trapped in the basement of the Palmerston Library Theatre, waiting for a magical elevator key.

Put differently, during the event we had embraced the power of our disabilities, and our performances were liberatory and felt revolutionary. We embodied Berne’s (2015) quote, “We know that we are powerful not despite the complexities of our bodies, but because of them.” We had found each other, and our shared storytelling highlighted the problems with society, celebrated the crip magic of our bodies and minds, and embraced the unique differences that each human possesses. We found what Wendy Walters calls “a kind of freedom…in being out of place.” To draw on Frantz Fanon (1952):

I came into this world imbued with the will to find a meaning in things, my spirit filled with the desire to attain to the source of the world, and then I found that I was an object in the midst of other objects. Sealed into that crushing objecthood, I turned beseechingly to others. Their attention was a liberation, running over my body suddenly abraded into nonbeing, endowing me once more with an agility that I had thought lost, and by taking me out of the world, restoring me to it.

Fanon feels the power of being out of place in a world that is violent and crushing. We were out of place in an ableist society and we were “in place” in a futuristic community of crip artists, storytellers, and activists. Yet, in the moment after this space was co-created, we waited for the elevator key, and those feelings of power began to dissipate. In the face of systemic ableism, the liminal space that we created, the space that had allowed for our being free, began to close.

In this other shrinking space, isolation began to return and the social exclusion and impenetrability of systemic ableism seemed to prevail: we could not leave the building to go home. We experienced the “lived reality of social and physical oppression” (Kuppers, 2009). The use of the phrase “I feel disabled” might have been used proudly during the performances. It might have conjured up synonyms: “I feel disabled/crip/magical/powerful/part of something/free/unique/joyous.” However, as we stood by the elevator for almost an hour, the phrase as uttered had changed from a sexy proclamation of pride and belonging. It changed in that moment into something that felt “crushing” (Fanon, 1952). We did eventually get the key, and we got to go home. Reflecting on all of the complex moments of that night, I have not been able to shake this “I feel disabled” comment.

Crip Your World helped to create a (however fleeting) space to be free together, to find power in difference, and to feel a sense of both self-determination and community. PDA celebrates the “myriad beauty,” as described by Berne, of racialized disabled people. Our work attempts to “subvert colonial powers” that push against us within the Canadian arts ecology, and within society as a whole. By centering racialized experiences of disability in our frame, mitigating the isolating effects of systemic ableism, and rejoicing in our creative resistance, we create work that is made out of love, of affection, and of celebration in a public sphere.

In 2014, we began to write about PDA. We developed a workshop series to offer free arts incubation space for BIPOC disabled artists and ran its first disability arts retreat in the fall of 2014. We continue to expand our work, at a pace that is manageable and that honours our crip bodies and minds. PDA grew out of love (our performances have truly been “public displays of affection”) and a need for disability justice within contemporary art practice. Together, we have created a process and way of working that is cripped and that works for our bodies and minds, and the experiences of embodiment of the artists that we work with. We have created spaces to innovate, develop, and share our creativity that are accessible to as many people as possible.

Yet, we are still doing this work in a disabling world; these artistic interventions seem essential and precious, while temporary, and prone to disappearing. The need for social change seems urgent to us. We continue to push for systemic change, connecting our work to a larger call from racialized disabled artists for an artistic revolution, by any means necessary.

Notes

- Mayworks Festival of Working People and the Arts. From their mission statement: “Mayworks Festival of Working People and the Arts is a multi-disciplinary arts festival that celebrates working class culture. Founded in 1986 by the Labour Arts Media Committee of the Toronto and York Region Labour Council, Mayworks is Canada’s largest and oldest labour arts festival. The Festival was built on the premise that workers and artists share a common struggle for decent wages, healthy working conditions and a living culture.”

- Abbreviation of Two-Spirited, Queer and Trans/People of Colour

- 2013 & 2014 saw a proliferation of Internet meme videos that begin with the framework, “Shit people say to…” illustrating perceived common experiences amongst a group of people identified by the video’s title. “Shit people say to sick and disabled queers” was part of this tradition and was created in two parts by Annie Murphy.

- One of the potential effects of anti-psychotic medication is the loss of memory due to anticholinergic effects. Coupled with benzodiazepines, anti-depressants with sedating effects and Parkinson’s drugs, all of which affect memory, I ended up with lasting and relatively significant memory loss.

References

Ahmed, Sara. On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press, 2012.

Art Gallery of Ontario. “Interview with artist LaToya Ruby Frazier, 2013 AIMIA AGO Photography Prize Nominee”. Art Gallery of Ontario, 2013. Video found online on September 27, 2015 at http://www.latoyarubyfrazier.com/site/category/video/.

Berne, Patty, “Disability Justice – a working draft by Patty Berne”. Found online on September 30 at http://sinsinvalid.org/blog/disability-justice-a-working-draft-by-patty-berne.

Chandler, Eliza. “Mapping difference: Critical connections between crip and diaspora communities.” Critical Disability Discourse/Discours Critiques dans le Champ du Handicap 5 (2013).

Colbert, Soyica D., “Black Movements: Flying Africans in Spaceships”. Black Performance Theory. (DeFrantz, Thomas F., and Anita Gonzalez, eds.). Duke University Press, 2014.

Cosenza, Julia. “SLOW: Crip theory, dyslexia and the borderlands of disability and Ablebodiedness.” Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies 6, no. 2 (2010): 6-2.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks [1952]. Edited by Charles Lam Markmann. New York, 1967.

Kuppers, Petra. Disability and Contemporary Performance: Bodies on the Edge. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Moten, Fred. In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition. University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

PDA. “Crip Your World Call Out”. Found online on September 30, 2015 at https://www.facebook.com/events/222983504576314/.

Sweeney, E.M. “(Dis)played: American Able and the Display of Contemporary Disability Art”. (York University M.A. Thesis), Critical Disability Studies, 2012.

Titchkosky, Tanya, and Rod Michalko. “The body as the problem of individuality: A phenomenological disability studies approach.” Disability and social theory: New directions and developments (2012):127-142.

Walters, Wendy. Post-Logical Notes On Self-Election. Black Performance Theory. (DeFrantz, Thomas F., and Anita Gonzalez, eds.). Duke University Press, 2014.

“Disability Futures in the Arts” is supported by the Canada Council for the Arts/Conseil des arts du Canada.

Back to Top of Page | Back to Disability Futures in the Arts | Back to Volume 15, Issue 4 – Winter 2021

About the Author

Syrus Marcus Ware is a Vanier Scholar, visual artist, activist, curator, and educator. Using painting, installation, and performance, Syrus works with and explores social justice frameworks and Black activist culture. His work has been shown widely, including solo shows at Grunt Gallery in 2018 (2068: Touch Change and Wil Aballe Art Projects in 2021 (Irresistible Revolutions). His work has been featured as part of the inaugural Toronto Biennial of Art in 2019 in conjunction with the Ryerson Image Centre (Antarctica and Ancestors, Do You Read Us? (Dispatches from the Future)), as well as for the Bentway’s Safety in Public Spaces Initiative in 2020 (Radical Love). Syrus has participated in group shows at the Never Apart in Montreal, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery, the Art Gallery of York University, the Art Gallery of Windsor, and as part of the curated content at Nuit Blanche 2017 (The Stolen People; Won’t Back Down). His performance works have been part of festivals across Canada, including at Cripping The Stage (Harbourfront Centre, 2016 & 2019), Complex Social Change (University of Lethbridge Art Gallery, 2015) and Decolonizing and Decriminalizing Trans Genres (University of Winnipeg, 2015).