Michael Northen

CONSENT TO BE SEEN: RIVA LEHRER'S REPATRIATION THROUGH PORTRAITURE

In October of this year, Haverford College cleared the forest of academic faces from the halls of the Sharpless Gallery in its Magill Library for a three month exhibition of the work of Riva Lehrer. The choice of Sharpless Gallery was a savvy one. In the spirit of "If the mountain will not come to Mohammed…" portraits of individuals who have been marginalized from society inhabit a transit area through which many of those visiting the library naturally pass. An art illiterate who generally passes by portraits without a second thought, I was captivated. Like most of those involved in the disabilities community, I had seen Lehrer's pictures on line a number of times, but the sense of energy generated by standing in the midst of them was a completely different experience.

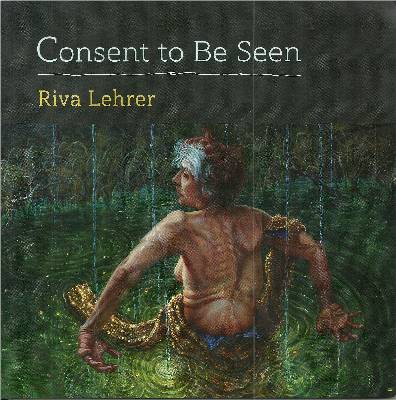

The exhibit, "Consent to Be Seen," is curated by Courtney Carter and Kristin Lindgren. Just as with past projects in which Lindgren has been involved such as What Can a Body Do?, "Consent to be Seen" is much more than providing gallery space. It is a truly educational experience. The project kicked off with a conversation between Lehrer and scholar Rosemarie Garland-Thomson who, for anyone remotely involved in disability studies embodies the cliché "needs no introduction." Haverford provided a beautifully rendered booklet to accompany the exhibit – a souvenir that anyone interested in disability art would want to own. Finally, in a lecture called "Presence and Absence: The Paradox of Disability in Portraiture" Lehrer provided an analysis of portraiture, its relationship to disability and the problems that it presents for the artist.

What emerged as most fascinating to me was the way Lehrer has chosen one of the most conservative and public art forms as a means of representing people with disabilities – a group that has traditionally been kept hidden or on the margins. As she explains, portraiture is about power. It confers upon those who are portrayed (i.e. the wealthy, who can commission it) a public recognition of their status. In an impromptu art lesson, illustrating this, Leher pulled back the screen being used for her presentation to randomly reveal a portrait of one of the college worthies. She asked the audience to look at all the vestiges of power from the black background and stern facial expression that let the viewer know they were not invited into his world to the symbols surrounding him that showed his authority. Lehrer also explained to her audience how almost from the beginning of art,portraiture had been a way of trying to confer immortality on one's self, a way of keeping in stasis the changes and eventual dissolution that time brings to the body. No wonder then, that most portraits are frozen and devoid of movement, excluding anything that would represent change –such as a mutable or atypical body.

The problem for Lehrer is how to use portraiture in a way that disability does not become an occasion for staring where the disability rather than the person becomes the subject. As Lehrer points out, against a background in which traditionally people with disabilities are represented in art as either medical models or the embodiment of some vice or character flaw, creating a positive, engaging portrait becomes problematic. This is where the title "Consent to Be Seen" takes on meaning. In Kristin Lindgren's words, "Her [Lehrer's] process of making is slow, conversational and deeply collaborative. She interviews her subjects at length and grants them a great deal of agency in how they are represented." For Lehrer, this is an evolving process. In one series of portraits,"Totems and Familiars," she asks subjects to choose objects or symbols that they want included in the picture with them. Her most recent series, "Risk Taking" addresses not just the risk for those portrayed but for the artist.Lehrer paints, leaves those being painted alone in the room with the work to make any changes they want to it, then comes back and adjusts the work further, a process that goes back and forth until finished. It is an overall project that Lehrer calls "Repatriation Through Portraiture."

in the opening night's dialogue, Garland–Thomson pointed out that for other minorities, it is understood that there should be writers and artists, but somehow disability until recently has not been recognized as appropriate to art. By taking portraiture, which by its very nature is realistic and recognizable, Lehrer has claimed the importance of disability to art and asserted further, that it is necessary as a way of enlarging our perspective and our conceptions of beauty.

"Consent to Be Seen" is up until January 20. In a city that offers many unique art experiences, this exhibit is one that you will find nowhere else. See it.