Sheila McMullin

ON COMICS AND DISABILITY

The most dominant narrative around "geek" culture is the "misguided" or "antisocial" youth nestled under a tent of blankets, way past bedtime, reading the latest The Incredible Hulk or X-Men comic book. Imagining their own strength and ability to righteously overcome the daily torments of bullying, fights at home, puberty, illness, and death, the youth sinks deeply into the superhuman realm. Reading comics are the stories of spilled pearls on a rainy night, nuclear explosions and mutant humans, flying men saving unsuspecting and nosy (yet beautiful and single) news reporters just a moment before disaster strikes. These are the stories of amazing feats and unbelievable kindness. They are terrific and exhilarating. For many, reading comics as a child was crucial to their adolescence, a huge part of helping them navigate social circles and environments. Comics were the constant companion, and as the youth matures into adulthood, comics are set aside as fond memories of yesterday.

But this story, indeed, is not the whole of the comics story.

* * *

When you're the only silent person in the room, no one else notices you, but you stick out like a sore thumb to yourself. And, like, the voices of other people become these really robust, physical things. Your voice is really the way your body is in the world outside of these [pointing to her own body] boundaries. Like, me, who I am, anyone who knows me, or loves me, or has talked to me for more than 5 minutes could hear my voice without my body being in the room and know that I'm there. And when I breathe in as I have to to live everyday, using my exhale, using that same breath that I just took from the air and then applying myself to it, I just feel so much more connected to everyone…So, I'd really like it for all of you to consider your voices and what they mean for you, for the people you love. Also, just how that feels in your body. You'd be surprised, it's very magical. Transcribed from Georgia Webber's, comics artist, "Raconteurs Presents Bodies," Performance.

Comics have a unique ability to intersect the visual with the textual, the routine with the surprise, to represent an otherwise unnoticeable sequence of events as the final piece of the puzzle. Comics have a long and textured history and along with the rise of blockbuster superhero movies, comics, today, are super cool again. And with this, over the past few decades have come a magnificent wave of autobiographical comics and graphic memoirs including personal narratives on disability. These comics honor, speak to, speak from the body which has been mitigated, regulated, intervened upon.

Comics on disability often ask more questions than they answer–the basis of any good art. They interrogate medical misogyny and racism, shaming, and unequal healthcare practices. They share intimate conversation on the effects of medicalized treatment and social stigma that the person and their families and loved-ones are living through. They explore our ability to connect with one another individually through building and showing consent narratives.

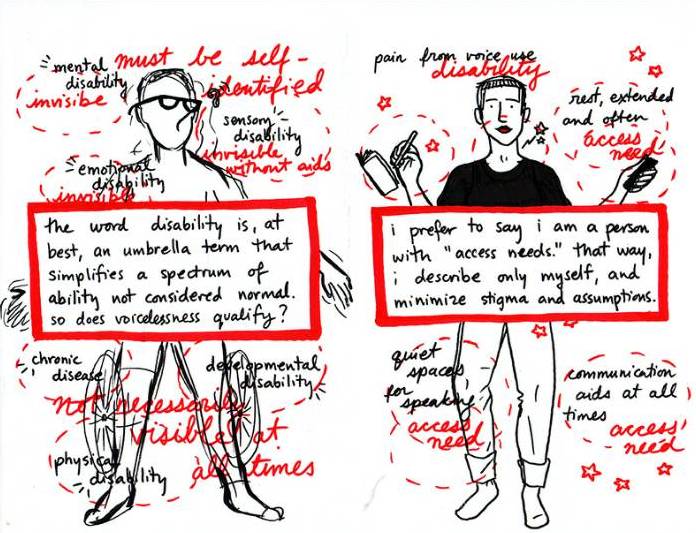

"Access" by Georgia Webber first published in Irene 4. Depicting two people's bodies encompassed by terminology describing and defining her pain and disability.

DUMB, an autobiographical comic series by Georgia Webber is about the artist's voicelessness due to vocal injury. Accused by a doctor of being a "vocal abuser," Webber tells the true and intimate story of her lived experience with access needs, ability to speak for only short periods of time a day, and recovery. This is an ongoing story with an ongoing recovery. Webber's series, like so many rich autobiographical comics and graphic memoirs brings to the forefront questions of identity and social stigma. Comics, being a multilayered visual interaction, allow for worlds to unfold within a single panel. There is a level of performance involved in both the reading of comics and the creation of it. As in Webber's above comic, Irene, the red sticks out like that sore thumb while also being a completely vibrant, beautiful firetruck red. For Webber, red represents when she's not speaking. And the red of silence comes filled with anxiety of whether or not her disability "qualifies," why this is even a conversation when there is pain, how this might elongate the process of getting the required assistance, the starbursts of pain, and its overwhelming presence. The black text places her understanding of herself onto the page and into context for others to understand and relate to as well.

Comics creation and consumption is an embodied experience. As readers, we are involved in multiple perspectives at once, invited to scan the body, participate. Webber says, "voice is really the way your body is in the world outside of these boundaries." In her presentation she meant that literally, I believe, but we can also take it metaphorically–use voice on multiple levels.

For disabled artists, artists with disabilities to create work focused on their own body through depicting what they know themselves to look like and presenting how one moves through the world is an act of embodiment. The comic is not the body, but is of the body.

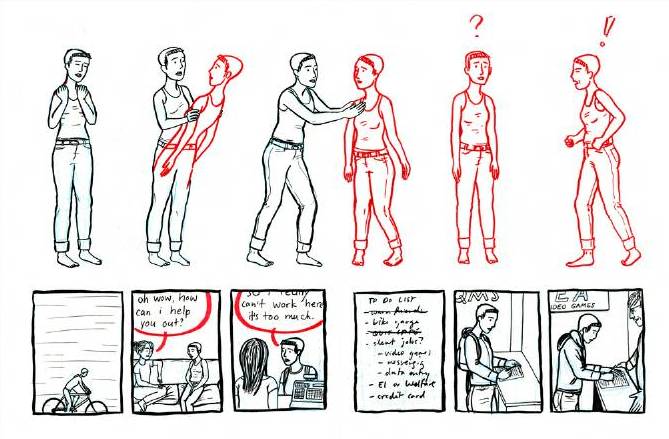

Georgia Webber, DUMB Issue 2 Depicting Webber, in pain, pulling a red version of herself out from herself and setting her aside while she completes her to-do list for the day.

Here, we see Webber literally setting herself aside whether to compartmentalize, have a conversation with herself, and/or parse the fact that she is having to quit her job and eventually go on welfare.

Representing your body on the page on your own terms is speaking truth to power.

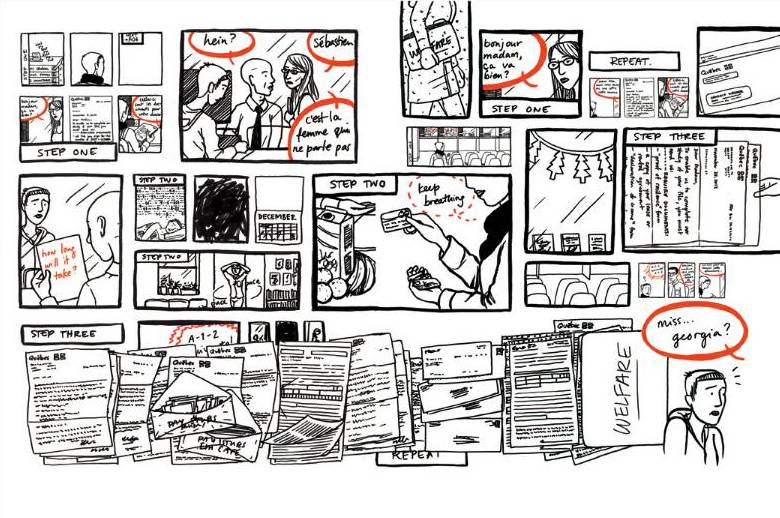

Georgia Webber, DUMB Issue 5 Depicting Webber's journey through applying for and living on welfare, the massive amounts of time spent, the paperwork to be completed, buying groceries, and standing in lines.

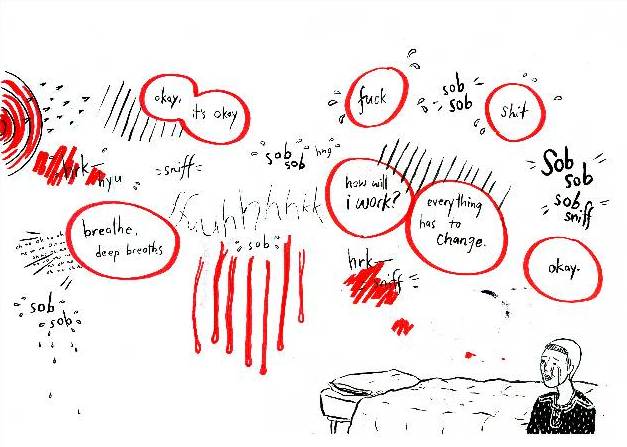

Georgia Webber, DUMB Issue 2 Depicting Webber crying, sitting next to her bed with anxiety about the future and how to pay her bills.

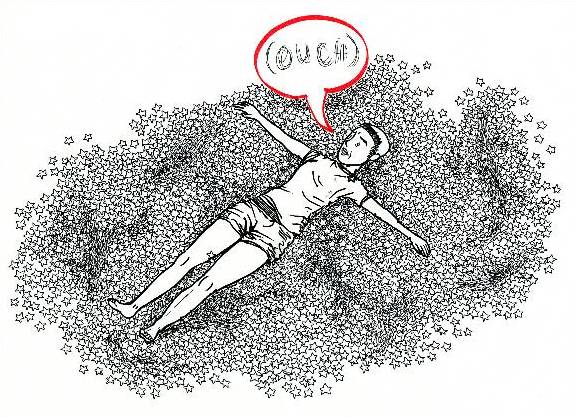

Georgia Webber, DUMB Issue 1 Depicting Webber laying on a giant bed of stars, which represent her pain, with a word balloon saying, "Ouch."

There are many crucial disability narratives of medical treatment focusing on technological intervention to help people become more mobile and independent. As well there are many stories that place disability experience in context with medical intervention as the way and only way to make people "healthy" or "normal" or "the same" again, often infantilizing, homogenizing, and rarely focusing on the individual lives of the people being treated. Autobiographical disability comics are powerful because they are the stories people share of their lived experience, their stories of being in the world day to day. Perhaps the artist chooses to include moments of medical intervention, treatment plans, the story of their caregivers, or therapy sessions within that story, but only because it is a part of their lived experience, not a biomedical model that is attempting to normalize bodies. It is curious to me why many are so willing to talk about how to intervene into people's lives but not actually talk to those people and about the nuances of their lives These autobiographical comics are opportunity to see differences in bodies and experiences placed into their own context on the terms of that living context. These comics are emphasis on the individual voice speaking for itself, deconstructing a socially manipulated understanding of disabled bodies exposing how, with such stealth, the medical gaze has dominated understandings of "valuable" bodies in literature and society.

* * *

Representations of chronic illness and the disability experience depicted in art, on stage, or in text, rarely avoid ableist narratives or stereotypes. In my work I strive to depict authentic representations of bodies and cultures that are not often shown. To see people with skin rolls, joint deformities, brown skin, or ambiguous gender presentations in art - particularly in ways that are complex and rich, nuanced and surprising is still rare. I am particularly interested now in futurisms, the stories and aesthetics of our future. Innovating shapes, cultures and bodies that don't exist yet - this is the pathway to transcending where our society is now.-ET Russian, comics artist

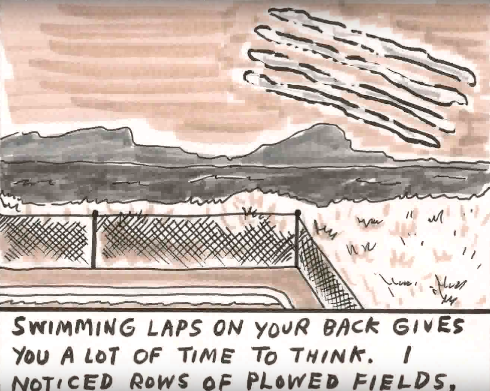

ET Russian, several panels from Secret Gem of the City though not depicted entirely. "I made Secret Gem of the City' a couple years ago (2013). It depicts an afternoon of two friends swimming together."

For me, comics became prominent in my life as I was exiting my teenage years. I was a budding poet and feminist. Used to exchanging images and metaphors as currency for meaning-making, reading comics was in my wheelhouse. I'm a big comics fan. I'm not a comics theorist, just a nerd, and by this point I think that distinction is important to quickly note. I don't draw my own comics yet, but these artists give me inspiration to draw my context and body onto paper. I find possibility and comfort in abstraction. At the intersection of text and image, a single comic panel reveals simultaneously what is spoken directly and subtly suggested. Comics, similarly to poetry, thrive in the in betweenness of moments. Comics demand reading into multiple layers at once, interrogating narrative function through multiple formats. Exploding the mundanity of otherwise unnoticeable moments into the essence of "of course," the pattern becomes an opportunity to break free. Comics are the artwork of intersectionality. Intersectionality defies hierarchy, and as a budding poet and feminist, I was into that.

ET Russian, artist and activist, says "Queerness and race, the disability experience, healthcare, science,

community dynamics, power and control, smut, and the spiritual realm are central themes in my work." Her comic

reads like a poem using the community pool almost as a dreamscape setting in  sepia tones. The comic opens with excitement for a lovely day of swimming at the speaker's favorite secret gem of the city,

which is an outdoor

saltwater pool right next to Puget Sound.

sepia tones. The comic opens with excitement for a lovely day of swimming at the speaker's favorite secret gem of the city,

which is an outdoor

saltwater pool right next to Puget Sound.  The comic depicts one of two friends with a scar along her spine,

another friend attending to her prosthetic legs. Once both are in the pool, floating and swimming on the surface,

the two friends turn their attention in different directions, but are both collecting things they have seen

during their time together. One friend finds treasures on the bottom of the pool like

rubber bands and coins.

The comic depicts one of two friends with a scar along her spine,

another friend attending to her prosthetic legs. Once both are in the pool, floating and swimming on the surface,

the two friends turn their attention in different directions, but are both collecting things they have seen

during their time together. One friend finds treasures on the bottom of the pool like

rubber bands and coins.

The other friend looks upward collecting clouds that look like dogs and vaginas. The comic, gentle in nature,

is filled with metaphor, examining the sweet and simple moments in life as creative and active wonderlands.

The water is an equalizer and connective, though harbors opportunity to move in your own way. The Everyday,

in Russian's comics, are transformed into art representing those simple, yet complex commonalities between

us all; the otherwise routine minuteness of The Everyday transformed into art that represents those simple,

yet complex difference between us all.

ET Russian, "The Chili Story" is a collaboration I did with Patty Berne and Ralph Dickinson of Sins Invalid in 2010. It is an erotic story of Patty's that Illustrated and edited into a video."

Coming out of the underground zine and indie comics culture is an activist intent to collaborate and help lift each other's voices up. ET Russian is an incredible collaborator. In an ableist society that more often than not denies the sexuality and sexual urges of disabled and chronically ill people, "The Chili Story" pretty much says it all already. Here I want to pay particular attention to the intention of pairing comics with interview. The illustrations featured have no thought or word balloons also narrating the drawing, which heightens both our attention to Berne's voice and the environmental/facial expression of each comics panel. The overlay of Berne's recounting of allergy and discomfort, struggle to get home quickly by public transportation, calling her caregiver to come over early to assist her once she gets home, flirtation and relieving herself in public builds the tension in our own bodies as we see the sweat on Berne's brow. Then the narrative slows, Berne's voice relaxes, the comic zooms in on the scene and the sensuality of the moment. The visual aspect of the comics video is sensually focused on lips and eyes while Berne notices a cute guy sitting across from her. The sweat from Berne's brow disappears. Auditorily, while Berne smiles and blushes, as the guy smiles and blushes, and as they eventually lock eyes, we lock eyes. Our eyes are staring straight into their eyes and we are flirting and smiling. There are no other sounds but Berne's voice in our ears whispering all those naughty things. As outsiders, we become intimately involved in the excitement of the moment and participate in the social taboo. And we get to be a little naughty and break some rules for a bit too.

* * *

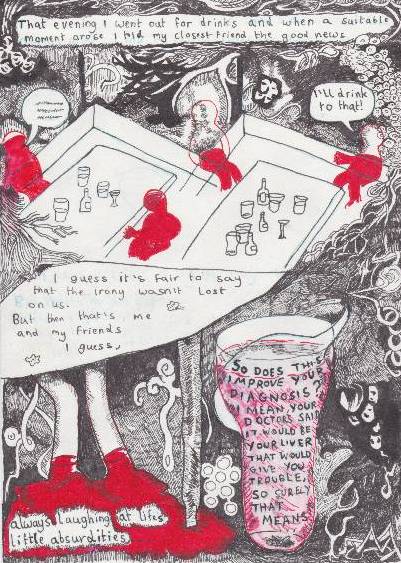

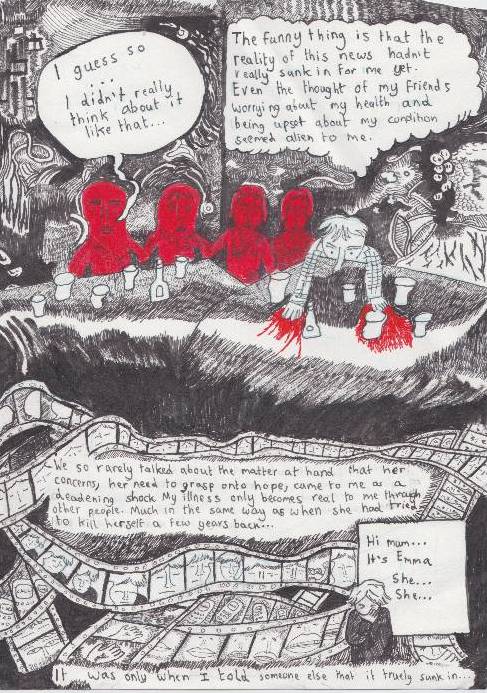

My comics started off by using humour to rally against the preconceived notions of chronic illness as represented through the media's preference for poster-child style images, but also took aim at the sometimes preciousness nature of the chronically ill, a competitive and often alienating "sicker-than-thou" attitude that I sometimes found whilst when stalking online forums for people with Cystic Fibrosis. Whilst I still see humour as a valuable tool in helping to foster an understanding of what it is like to understand these conditions, I'd like to think that my stance on the political and social implications of this has mellowed somewhat as I have grown older. I am less easily offended by people's misunderstandings and perhaps a little less angsty and self-involved (although not entirely!). I like to think this sequence here (from a sadly unfinished and unpublished second issue of my autobiographical comic series) marks the beginning of this shift of thinking in which I start to consider my illness from point of views other than my own. For example this sequence makes a direct reference to my close friend and collaborator Emma Jeremie's experience with depression, which in turn becomes a filter for my own experiences and thoughts, especially those regarding my own mortality. My own academic work has somewhat overshadowed my comics of late, but being asked to submit pieces to this article has reignited my creative guilt in such a way that I envision finally getting down to a new issue which tackles these themes of mortality and growing up (having recently turned 30), themes which I hope will resonate with both those with chronic illness and those without. -Andrew Godfrey, comic artist

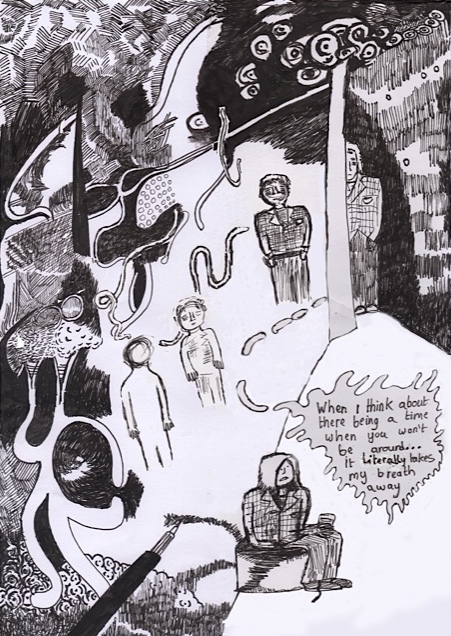

Andrew Godfrey, comics sequence from "Sicker Than Thou," an autobiographical account of living with Cystic Fibrosis.

Comics, despite the medium, are never flat objects. Comics use perspective and angles as narrative tools. Chronic illness shifts one's orientation in the world. Through illness perspective and drawn perspective, Godfrey's comic "Sicker Than Thou" provides a macabre, yet salient intimacy between artist and reader.

While ableist thinking seems to avoid the fact of our mortality, these comics are directly confronting the artist's continual and ongoing conversation with his own mortality as living with Cystic Fibrosis. Godfrey's comics give insight into how he orients, while simultaneously investigating how his friends do not typically confront these same thoughts with as much frequency as him. Godfrey, like the "Chili Story" uses comics to talk about the things we're not supposed talk about.

Embodiment of drawing and writing is an attempt at translating what is intuitive to our hidden lives and conversely an attempt at organizing what is so completely intangible. The process is physical and marks the passage of time. The passage of time is a major theme in Godfrey's comic. One intriguing aspect of Godfrey's comics is the way in which we see the artist literally draw his process and move through process on the page. In "Sicker Than Thou" we see revelation and thought as if it were in real-time. We never know when we're going to arrive. Until the last panel in the sequence, the comics are all ornately decorated with patterns and etch marks creating a boundary around the scene of the friends as they move about the bar. There is a vibrant red, perhaps blood or a life essence, which seems to fill some of the people depicted, while spilling out of Godfrey himself completely. A film reel splices the scene of the second panel, perhaps an allusion to the story Godfrey is playing and replaying in his head about his friend's attempted suicide or his last call with her and/or his mother. When we arrive at the final panel the characters become more like sketches and rough markings. We are given much more white space which is occupied by the word balloon and the heavy expression of breath being taken away. As readers, we hold our breath for a moment waiting for what comes next. The sense of taking one's breath away while thinking about another's mortality instills the thought of if you won't be around, how could I? Even more, we do not know exactly who is thinking that thought, implying that perhaps, everyone is inside their private minds. Godfrey makes what is private, public and at the bottom of this same panel, we see a drawing of a pen which seems to be actively drawing the comic we are looking at. We realize that this whole time we've been reading toward a present moment and an expression of loss, concern, conflict in progress.

The comic situates us within a double orientation. It is drawn from the perspective of the artist while drawing at his desk looking down onto the paper. That is, looking down on the scene from above. Quite literally, we are seeing the scene from the "creator's" line of sight. Take "creator" as metaphorically as you'd like. I envisioning Godfrey in the act of making and thinking about this piece through that pen while simultaneously be given an invitation from the artist to see my hand extended outside of the page holding the pen drawing the comic with him. Godfrey confront artifice through layers of removal as opportunity to be reflective and give space to memory. As Godfrey writes, "It was only when I told someone else that it truly sunk in." Simultaneously Godfrey is remembering telling his mother of the trauma and as readers we are also a part of the equation of what is being sunk in rallying against poster-child style images. These comics are a rupture of infrastructure. Similar to Webber's piece of setting herself aside, Godfrey takes a microscopic look at himself from above.

Poignant to all autobiographical comics, but in particular to Godfrey's, these pieces shine light on personal information and speak to the private lives of others. Godfrey's comic pushes up against questions at the core of autobiography: which part of other people's stories are ours to tell because they have uniquely and profoundly influenced our story as well? In a 2013 panel discussion with Godfrey and his friend, Emma Jermaine, mentioned in the comic, tackle this question (you can listen to the panel "But Who Is This Story For? : Representation and Responsibility in Autobiographical Comics." here). I am not privy and have no authority to speak to their work relationship or friendship, but from an outsider's perspective it seems like Godfrey and Jermaine as collaborators have built such a safe space for one another, that sharing both of their stories publicly and widely is also partly about them coming into even better knowing of themselves and of their friendship and care for one another. And that others with similarly lived experiences or intentions know they are never alone. That telling our stories only makes us more powerful.

Comics thrive in multiplicity, asking intimate questions of what is private, what is public, how we know what we know, and how to more fully understand ourselves by sharing what we need to with those we trust and eventually with those we may never know personally. They represent our bodies on the page in their own context, using art as a thought process to navigate and express our bodies.

Reading these comics and loving on these comics constantly remind me that representing our own lived experience with the intention of sharing and having conversation is and can be empowering for the entire community. That reating art is an act of embodiment. The autobiographical comic and graphic memoir unsettles convention, is revolution.

* * *

Want more comics and comics communities to check out? Here's a short and totally incomplete list!

- For those interested in the intersection of poetry and comics and the juxtaposition of image, Russian's "If The Glove Fits" is a visual poem and thoughtful journey of a pair of gloves as they move from one person's hands to the next. The nonverbal visual poem is originally published in the comic collection THE HAND.

- THE_HAND is a Seattle-based cartoonist collective of which ET Russian is founding member.

- Ink Brick: a micro press for comics poetry

- Cripping the Comic Con

- Graphic Medicine: International conference on the intersection of comics and healthcare.

- "Shapereader, is a repertoire of forms and patterns that constitute an attempt to translate words and meanings into tactile formations. It was designed from scratch with the goal to transpose works of graphic literature to a blind and visually impaired readership, Shapereader advocates for new publishing grounds and challenges visual predominance of graphic storytelling."

- Death, Disability, and the Superhero: The Silver Age and Beyond by Jose Alaniz, comics scholarship.

- Carol L. Tilley's "Comics: A Once-Missed Opportunity" for more comics scholarship.

- Laurie Clements Lambeth September 2015 Wordgathering essay

- John Porcellino's The Hospital Suite and Ellen Forney's Marbles were among the first graphic memoirs I read a bout disability and chronic illness where medicine was not inserted as THE way and only way to treat impairment or illness.

- Kaisa Leka's Graphic Memoir I am not these feet on amputation, learning to walk again, and all the life in between.

- Cece Bell's El Deafo about her childhood, growing up deaf, and the hearing aids which give her superpowers, transforming her into El Deafo!

***All images and quotes are used with expressed permission from artists.