Laurie Clements Lambeth

FROM METAPHOR TO METAPHORPHOSIS

As a child, drawing cartoons was all I wanted to do, but I essentially abandoned visual art shortly after I was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis at 17, returning to art through doodles and illustrations here and there, but no longer seriously pursuing it. Instead, poetry, which came to me in the wake of early symptoms, became my new art form. When MS affected my ability to read, I began drawing again. Now, years later, I'm finding that drawing and painting on a tablet is far more forgiving than paper or canvas used to be, where every mistake, no matter how much I'd try to erase it, remained. On a tablet I can erase mistakes completely and experiment more with new methods, new lines, and different styluses. Working on a tablet requires less pressure and strength, as well, than working with traditional materials, bringing access to typing (my first reason for an iPad), writing by hand, and drawing.

I'm a huge fan of Alison Bechdel's graphic memoirs Fun Home and Are You my Mother?, as well as more illness-related graphic memoirs like David Small's Stitches , Steven Seagle's It's a Bird, and, of course, Harvey Pekar's Our Cancer Year. Like Bechdel and Small, I prefer drawing my own panels, but I lack their talent, expertise, and patience. A convention of the graphic memoir, at least to my mind, seems to candidly offer a lot of narrative or procedural information I might ordinarily leave out of poetry or even lyric prose, so it's liberating to explore new subject matter through the genre. The shifting image, whether zooming in through successive panels or breaking down a process step-by-step, affords graphic memoir a sense of momentum and tension, perhaps akin to the ways enjambment can offer counter-movement or intensification within a poem. Another convention of the genre is far more obvious: the work of imagery in graphic prose is accomplished not so much through language but through the actual sketched image on the page. I am including these graphic moments in my hybrid memoir, at times offering graphics and at other times using prose, depending upon which "language" best fits the experience.Hypertonia

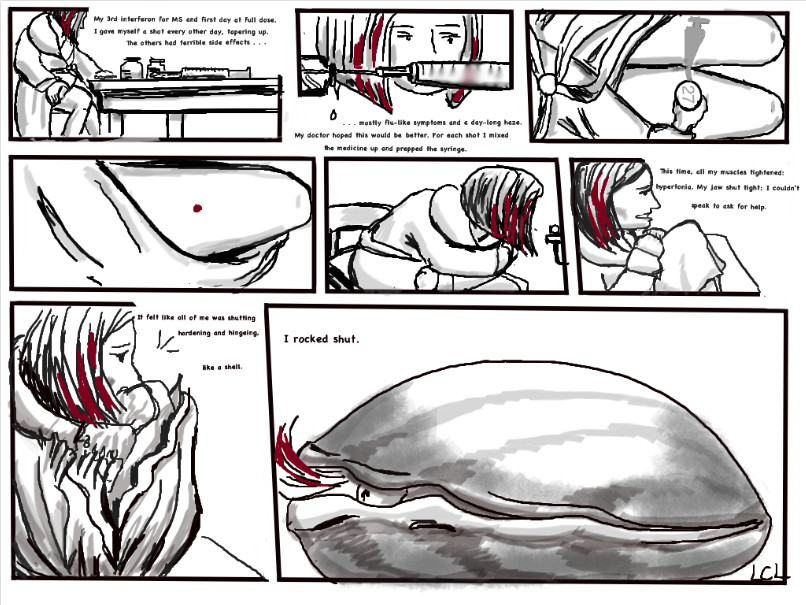

This was the first attempt I made to illustrate a moment through multiple graphic panels rather than words. It came 2 years after the event it describes: my first, full-strength self-injection of a new medication, after weeks of titrating up. I knew about (and felt) the flu-like side effects, but buried deep inside the package insert's list of possible effects is "hypertonia," an involuntary tightening of muscle tone: spasticity turned up to 11. As my muscles clamped shut bit by bit, I felt like I was becoming a shell. "I rocked shut// As a seashell" is Sylvia Plath's territory, a metaphor in her poem "Lady Lazarus," and though those lines kept reverberating through my mind throughout the event and long after, I felt as though I was a literal shell clamping shut, less metaphor than metamorphoses.

In the same way that I used prose fragments in my book Veil and Burn to convey experiences related to vision loss and fear of memory loss—areas I could not quite explore in poetry without risking melodrama, experiences that seemed tuned to a different kind of language, spare and tight —I found that through visual art, specifically graphic memoir, I could access yet another kind of language for experience, finally being able to convey the event entirely as it felt, through sometimes jarring visual images accompanied by sparsely-worded captions. My graphic piece "hypertonia," seems less maudlin than it might have been in poetry's territory, given the expectations built around each genre. I found that the sequential drawings also allowed me to be more overt than I allow myself to be through language. I do have a poem entitled but the poem glances off of this moment and uses it to go somewhere else. To read the poem you can go to Tupelo Quarterly, or to Wordgathering contributor Liz Whiteacre's Poets Studio , where I compare the graphic and poetic representations of the event.

Origin Story #1

In this piece I am responding to the ways that memoirs addressing illness and disability are expected to follow chronologically from the originary moment of diagnosis, injury, or birth through a trajectory of either overcoming or decline or cure, and I want to resist that utterly(!) by pointing to multiple possible originary moments (which I hope to illustrate through multiple versions of this panel, the hand breaking apart, branching open). I don't know, for instance, precisely when I developed multiple sclerosis. The first sensation that sent me to the doctor was numbness in my left hand, but I had also developed optic neuritis, quite often the first MS symptom people experience, when I was 11, and I went blind temporarily in my left eye. Since my case of MS was indeed classified as pediatric, could that initial blindness actually be related to MS, my "first" episode? If I mention that this occurred after my friend and I had been hitting a tethered tennis ball (Zim Zam) as hard as we could with paddles, and that the ball hit me in that eye, how does that change the story's genesis? One MS specialist was intrigued when I told him that as a kid I was hospitalized for extreme nausea and dizziness which was later diagnosed as labyrinthitis, inflammation of the inner ear. No other doctor has found this experience to be related to multiple sclerosis, even when MS-related dizzy spells clocked me in the head repeatedly for a few weeks in my twenties. It appears that there are no clear answers, so why should I embrace the certainty of a single generative moment?

My memoir so far follows a different trajectory—more fluid and cyclical, more akin to relapsing-remitting MS, dipping into and out of prose or graphic panels, crossing timelines, echoing everywhere, offering fewer answers than questions … which feels right. To me it seems that graphic expression of my fluctuating, multifaceted disability can condense time, uniting the cartooning aspirations I held as a kid with the writing I've tried to hone as an adult, and pushing me to explore further.