Michael Northen

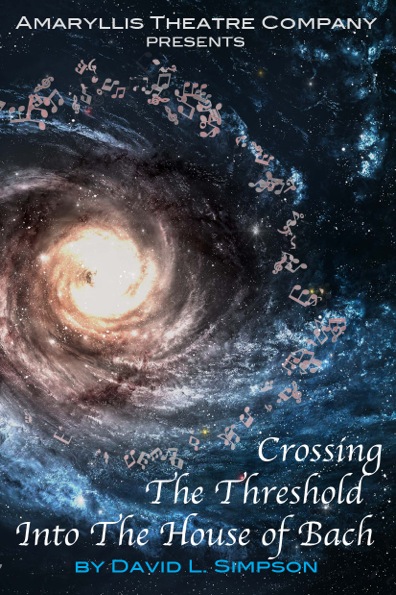

CROSSING THE THRESHOLD INTO THE HOUSE OF BACH

When David Simpson's play Crossing the Threshold Into the House of Bach premieres with Amaryllis Theater this month, it will be a testimony not only to the playwright himself but to the strength of community. Many attending the opening will know that Simpson, a poet known widely in the Philadelphia area, was diagnosed almost two years ago with ALS, but far fewer will know the journey that the play has taken to production.

David Simpson, who with his twin brother Dan Simpson was born blind, channeled his artistic impulses throughout most of his career towards poetry, vocal music, and, especially, the organ. As the play's director Mimi Kenney Smith recalls, it was not until she asked him to read for a part in the play Blood Guilty with Amaryllis in 2006 that he was bitten by the bug to write a play as well. After the production of Blood Guilty, where he acted with Michael Toner, Simpson, with no other dramatic experience up until then, determined to write a play himself.

With grants from the Independence Foundation, Simpson attended playwriting workshops while formulating his ideas for the play. In addition to Smith, who had been involved from the very beginning, Simpson was mentored by poet Molly Peacock, long a supporter of both Simpson brothers' work. Peacock had performed her own one-woman show and it was, in part, seeing her production that edged Simpson towards a similar format for his own. He also gained greatly from the experience of playwright, Michael Hollinger, who eventually took on the role of dramaturg for the current production. It was Simpson's plan to perform his own play even after his diagnosis of ALS, but as time passed that design seemed increasingly unlikely. In order to ensure that the production became a reality, his old colleague Michael Toner agreed to take on the role.

As the play opens Dave (played by Toner) is seated at an organ trying to perfect his playing of Bach's Von deinen Thron, the last piece for organ that Bach composed. His frustration is clear as he recalls his French organ teacher Andre Marchal’s genius and the seemingly near perfection with which his mentor had played the piece. The audience hears the music but what would not be immediately clear to them — at least without program notes —would be that the music they hear was played by David Simpson or that the fact that they can hear the music at all was a collaborative process. Mimi Smith wanted to use Dave's own playing of the Bach piece for the stage but at the time production started his playing of that piece had not been recorded. Sound engineer John Stovicek recorded and digitized Simpson's playing but as the character of Dave in the play says, "I've given up on pain but not on perfection." Stivicek, Smith and others, worked day after day, often at Simpson's bedside to bring it as close to the author's ideal as they could.

Organ playing is only one way that the use of tapes is employed in the play. As a blind man, Simpson had used audio recordings his entire life to gain access to what others learned visually. When he began writing Crossing the Threshold, one of his first decisions was to bring his own experiences to the audience by minimizing the visual and relying on sound. So while the stage is relatively bare with Dave, the organ and a few chairs, much of what the audience experiences during the play comes by way of audio recording, filling in such things as memories in the form of voices from the past or external sounds.

Like most of the audience viewing the play, Dave is a secular person living in a secular world, who long ago abandoned those concepts of religion that he was taught in Sunday school. As the play progresses what he discovers through playing Bach — for whom religion and music were inseparable— is that it is impossible to approach an understanding of Bach without religion becoming a part of him. The autobiographical nature of the play and the knowledge of the writers' physical trajectory, of course, bring a heightened intensity to this realization, one that life itself has written into the script.

Within the world of disabilities studies one often hears the distinction between the medical model of disability and the social construction model of disability, the former being roundly criticized and the latter embraced. This can be baffling to those not involved with the disability since it would seem obvious that a physical impairment is a very bodily phenomenon. The core of the criticism comes down to the problem that a medical model of disability views disability as the problem of an individual and the responsibility for dealing with it lies with that individual, while a social construction model sees disability as society's response to impairment or unconventional bodies. It places the responsibility for inclusion on the community.

Among the arts, theater is arguably the one most engaged with community, and Amaryllis Theater is no stranger to collaboration with the disabilities community. They have produced performances of Lynn Manning's Weights, done reading of Paul Kahn's The Making of Free Verse and organized the productions of work from Inglis House writers/actors, all of whom were in wheelchairs. David Simpson lends his own testimony to this activism when he writes:

Through Mimi and Amaryllis, I learned that a theatre could provide audio description for blind audience members, as well as captioning and American Sign Language interpretation for those who are deaf or hearing impaired. Moreover, Amaryllis offered playbills in Braille and included actors with disabilities in its productions, all the while maintaining a commitment to producing the highest caliber of art.

Collaboration with writers and actors with disabilities is not an act of charity. It is an inclusion and reciprocity that enriches the arts for all, providing alternative perspectives and insisting that creativity be stretched. The results, as David Simpson's Crossing the Threshold Into the House of Bach demonstrates, speak for themselves. While it is true that ultimately every human being must pass over the threshold into the house of Bach alone, having that sense of community on the journey there makes the crossing easier.